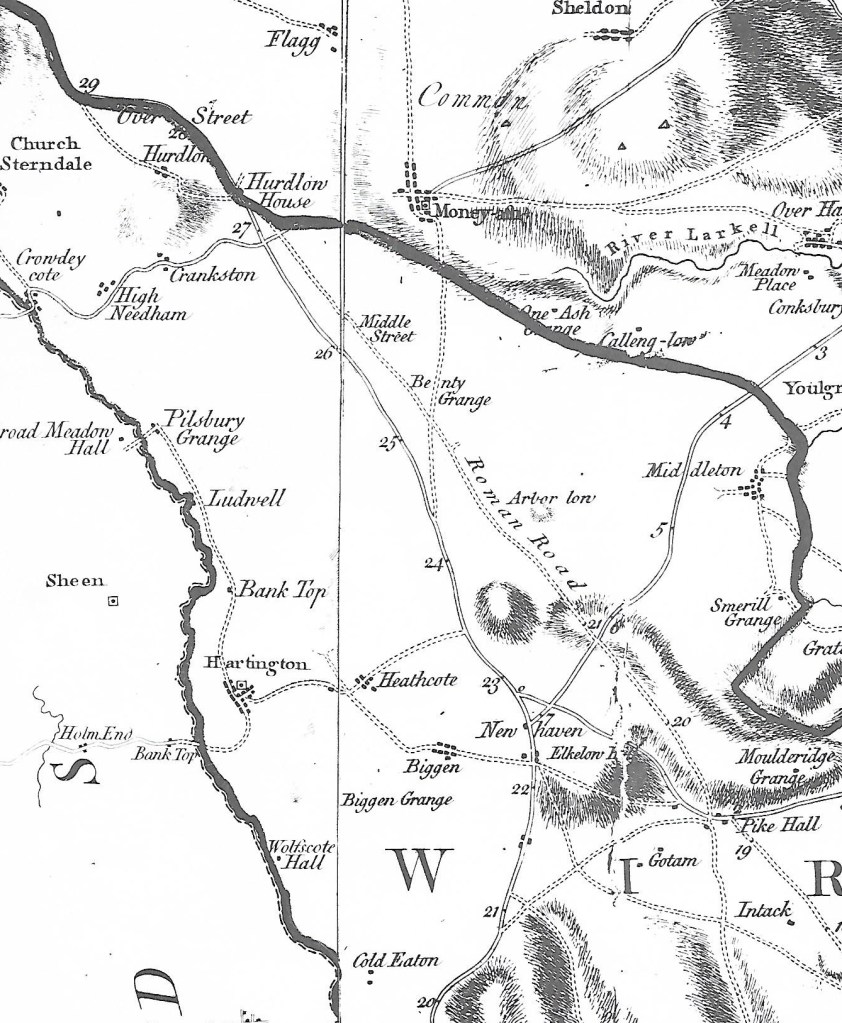

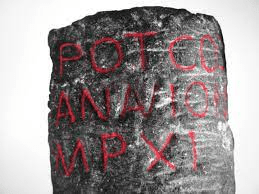

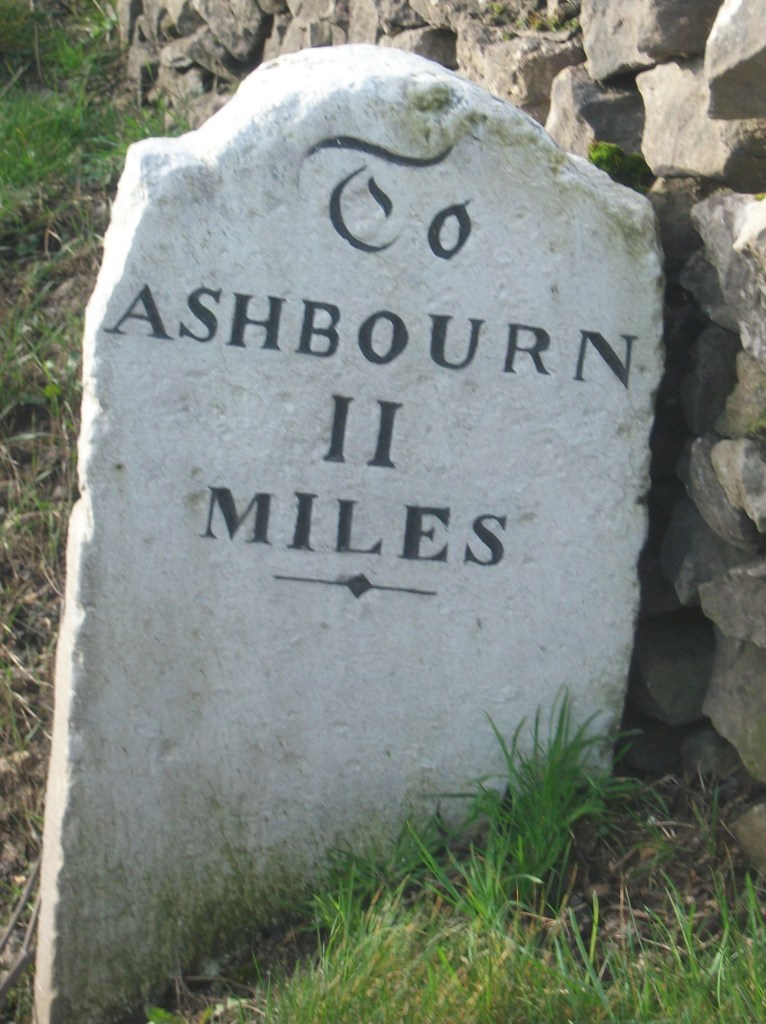

John Farey (1766-1826) was a geologist and mathematician who wrote an extensive report on agriculture in Derbyshire, early in the nineteenth century. To research the subject he clearly had to travel widely, and this experience led him to produce a shorter report on the roads of Derbyshire in 1807. Finding his way around was clearly a concern, as he writes scathingly about the state of the milestones (‘too much neglected’) on account of the lack of maintenance: instead they are ‘shamefully defaced’ by ‘idle and disorderly persons’. Similarly the ‘way-posts or finger boards’ (i.e. signposts) ‘are entirely defaced’ with ‘scarcely a single inscription legible’. Despite this anti-social behaviour, Farey also notes the use of Latin on some ‘wayboards’, notably Via Gellia in Bonsall Dale and ‘Equus Via Longford’ near Shirley.

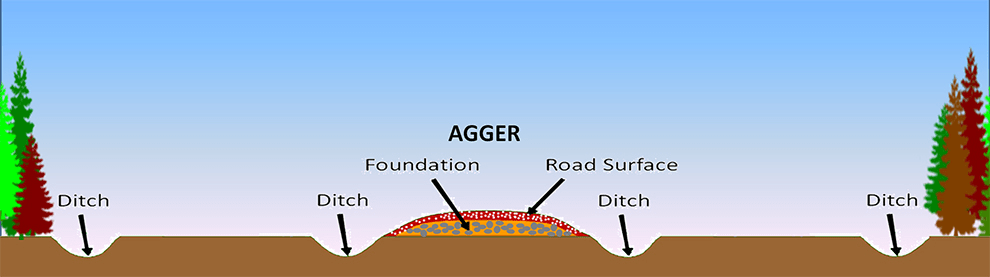

He does, however, approve of the ‘many excellent Inns’ on the county’s turnpikes, and mentions the Rutland Arms at Bakewell, the Eagle and Child at Buxton, the King’s Arms at Derby and the New Inn at Kedleston, among others. As a geologist he notices that Peak Limestone is hard and so good for road building, but that Magnesian Limestone is easily crushed into a ‘gritty mire’. This was probably the first time that a such scientific approach to road construction had been made.

Farey also approvingly describes a feature of roads in the horse era that few historians have noted. He sees that ‘throughout the County’ cottagers’ children, women and old men are seen ‘perambulating certain lengths of the public Roads’, which they patrol regularly ‘carefully picking up every piece of horse-dung that falls’, and then carry their collections in baskets on their heads for sale to local farmers. Apparently shepherds on the few remaining commons did the same. Farey does not provide details of the going rate for a basket of horse dung, but the practice is an indicator of the depths of poverty in the pre-industrial world. He goes on to complain of the practice of turning cattle and horses out into the lanes to feed on the verges, saying that his horse had been upset by these semi-feral creatures. However, despite his criticisms, Farey rates this county’s roads positively: ‘… after paying a good deal of attention to this subject in most parts of England, I think few of the counties excel Derbyshire as to its roads …’ .