A group of Ripley cyclists about 1914

Bicycles only became practical transport in the 1890s, with the arrival of the chain-driven ‘safety cycle’ fitted with pneumatic tyres. Priced at about £12, for the first time they brought leisure travel within reach of the skilled working man or women – playing a significant role in female emancipation. Pioneering cyclists organised cycling clubs for weekend excursions, partly due to the state of the roads at that time, which caused frequent punctures. In the north the left-wing Clarion movement – strongest in Sheffield – organised a cycling association which held its first meeting at Ashbourne in 1895. Open to both sexes (unlike others) they saw their outings as an opportunity to spread socialist tracts around the countryside. Still in existence, the Clarion Cycling Club has (sadly) now dropped socialism from its masthead.

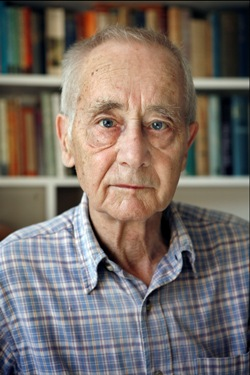

In the Edwardian period writers such as Thomas Hardy, HG Wells and DH Lawrence wrote of the pleasure and independence of cycling, which must have been greater at a time when cars were rarely seen. But a more recent writer has recorded his love of cycling from Nottingham into the Peak District. Alan Sillitoe (1928-2010) wrote that he first bought a bicycle at the age of 14, and headed for Matlock via Eastwood (before the modern A610 was built). He free-wheeled down to the Erewash and then pushed the bike up part of the hill to Codnor, ‘and many another walk with the bicycle before coming into Matlock’. Clearly his bike was lacking the gears that today’s cyclists take for granted!

Alan Sillitoe, author of ‘Saturday Night and Sunday Morning’

Sillitoe writes: ‘I’d go on Easter weekends through Bakewell and Buxton to Chapel-en-le Frith, and back to Nottingham via Chesterfield and Clay Cross, sleeping in fields and barns by the roadside, or under the lee of those rough stone walls, marking off the fields, thinking the hills beautiful and restful, but in no way hating the small hilltop mining towns and settlements when I got back among them … at Easter the road was often wet, and the wind could be bitter enough, but the real impulse was to wear out the body after a week in a factory, and reach as far a point from Nottingham as a bicycle could go in one weekend’.

Source:

Sillitoe, A. Lawrence and the Real England. A Staple Special (1985)