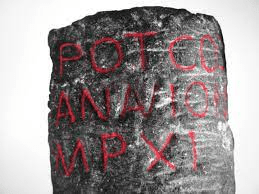

This stone, partly broken, can be found lurking in the hedge of the minor road that links Fritchley with Wingfield. Although partly broken, one side still reads ‘Winfiel(d)’ and the other ‘Crich’. Easily mistaken for a milestone, this is actually a boundary stone marking the limits of these two parishes, marked BS on Ordnance Survey maps. The boundary here can still be followed on public footpaths, southwards to a footbridge over the River Amber and Sawmills, northwards (briefly) to Park Head. The OS maps mark the boundaries with black dots, though they can be difficult to see.

The parish system of local government is thought to have been established in Saxon times, although individual parishes were originally much larger. In the past, parishes were the only kind of local authority that affected most people’s lives, being responsible, for example, for road maintenance. Therefore the limits of the parish were important, and in a largely pre-literate society this knowledge had to be handed down orally, hence the annual perambulation known as ‘Beating the Bounds’. This involved the priest, various landowners and some unfortunate young lads, whose fate was to be beaten at critical points so they would remember them. Who knows whether this beating was symbolic or real?

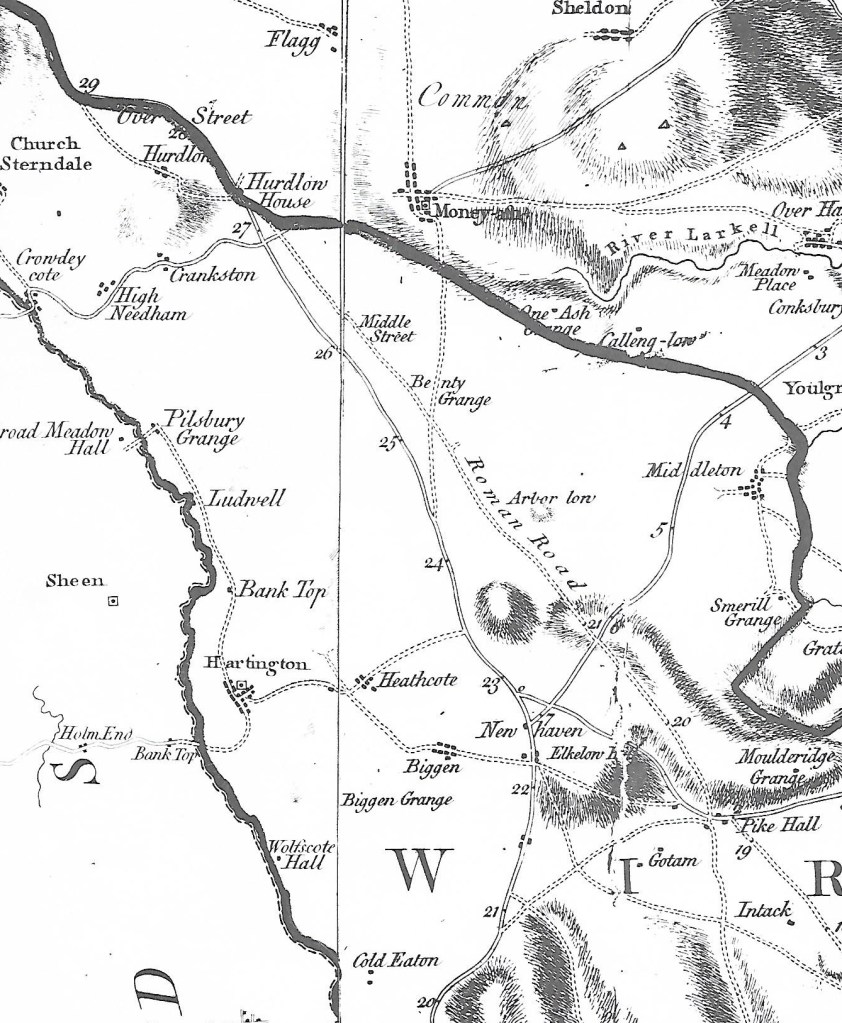

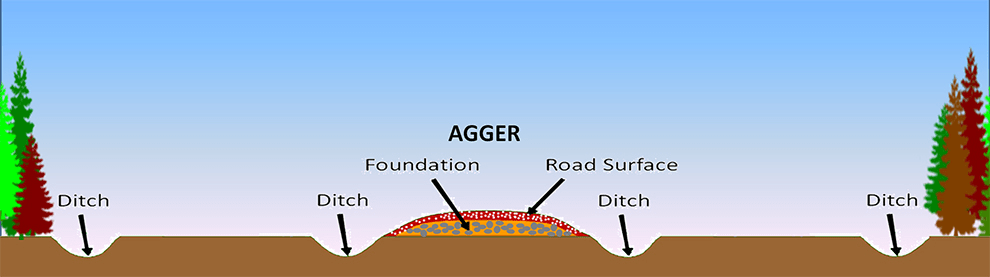

Rivers and streams were often used as boundaries, since they were unlikely to move very much, but as they were not always available other marks, such as large trees, might be used, and clearly boundary stones were sometimes also needed. Where the line of a road (or footpath) is a boundary it suggests that the road is very ancient and important, such as sections of the old Roman road (The Street) running north from Pikehall, which was in use for at least 1,500 years. Today the custom of bounds beating is obviously redundant, but in places it has been revived as an enjoyable excuse for a group walk, as in the Macclesfield example above. More locally, a WEA group from Crich re-enacted the ceremony in 1984, and produced a very helpful written account of their route around the 14 miles of the parish boundary. See: https://www.crichparish.co.uk/PDF/beatingbounds.pdf