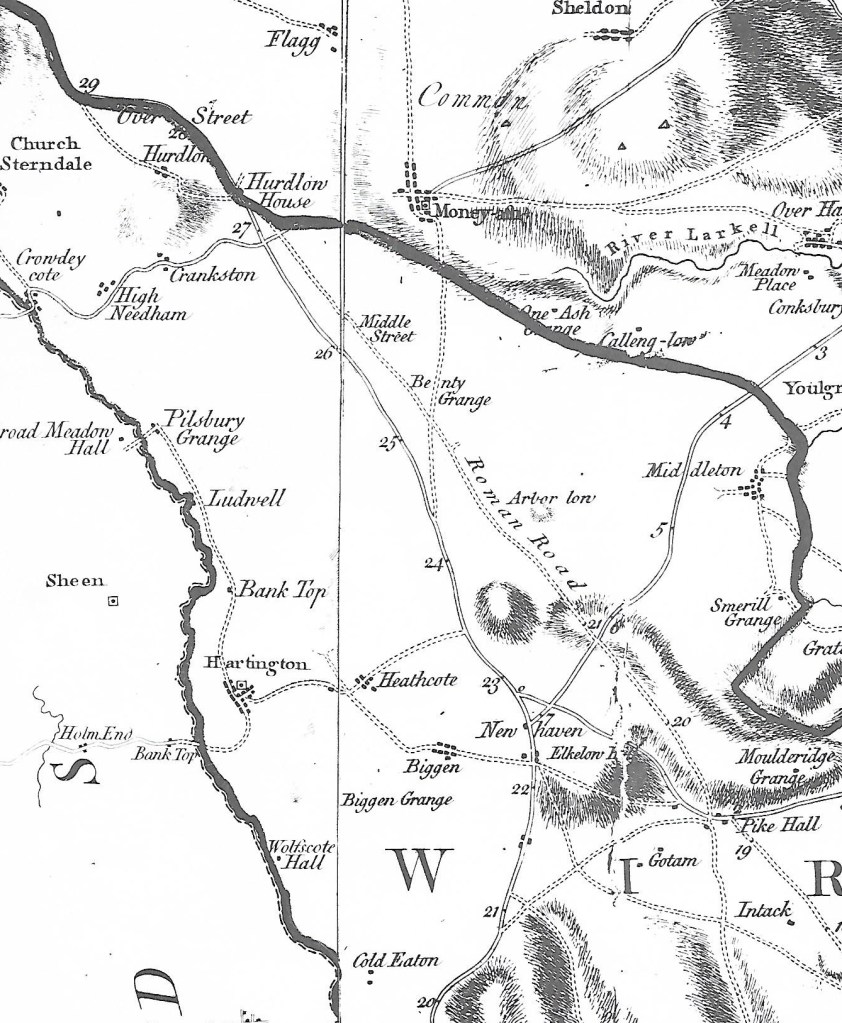

Butterley and Ripley from Sanderson’s map of 1835

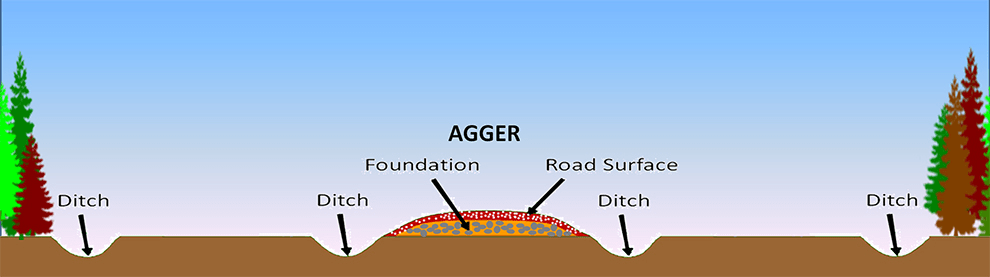

The Butterley Tunnel, shown on the map above, was one of the biggest engineering challenges in the construction of the 14 mile-long Cromford Canal, opened in 1794. Just over 3,000 yards (1.75 miles) long, the tunnel was only eight or nine feet wide, for reasons of economy. Clearly this did not allow space for a tow-path, and so the horses had to be walked over the hill, on the Tunnel Road which can be seen near the centre of the map. To avoid underground collisions there were strict rules for using the tunnel in different directions, for example barges travelling west could only enter the tunnel between five and six in the morning or one and two in the afternoon. They were expected to clear the tunnel in at least three hours. As the barges had to be ‘legged’ through, with the bargees lying on their backs, you can only hope they didn’t suffer from claustrophobia! The view of the eastern tunnel mouth today, below, gives an indication of how narrow the opening was, although when in use it would have been deeper than this photo sugests.

The Butterley Ironworks, a major factor in the growth of Ripley in the nineteenth century, was founded at the same time as the Canal was developed. Coal was mined from several pits in the area and iron ore was also quarried locally. The company went on to develop forges and blast furnaces at Butterley and Codnor Park. Clearly the canal was vital for the business, carrying both coal and finished products: an underground wharf still exists so that boats could be loaded directly below the Ironworks. One iconic product from Butterley was the steel frame of the roof of St Pancras Station.

At the end of the nineteenth century the tunnel suffered from mining subsidence, with rock falls, and was finally closed to traffic in 1900, so that the Cromford Canal, already suffering from railway competition, was cut in half. Today the Tunnel Road can be walked from the back of the Ripley Police HQ to Golden Valley, and several brick air shafts can be seen on the route. A path to the north of this road leads to the Britain Pit (photo above), whose winding wheel and engine house give an indication of the industrial past of the area. Sunk in 1827, this shaft is now part of the museum of the Midland Railway Centre, which operates trains on both standard and narrow gauge tracks nearby.