In summer 1918, near the end of the First World War, DH Lawrence and his wife Frieda were forced to move from the south of England to Derbyshire, in the Midlands he thought he had escaped from years before. Out of work and hard up, having been harassed by officialdom for his wife’s supposed pro-German sympathies, Mountain Cottage offered them a refuge, with the rent paid by his relatively affluent sister, Ada, in Ripley. Refuge maybe, but in those days not a luxurious one. Steep field paths ran downhill to the Via Gellia, Cromford and Matlock Bath, or the road through Middleton would take him to Wirksworth station a couple of miles away. Water had to be fetched from a well in the lower garden, and of course there was no electricity, though this would be normal in rural Derbyshire at that date.

On Friday, December 27th, 1918, Lawrence wrote to Katherine Mansfield:

“We got your parcel on Christmas morning. We had started off, and were on the brow of the hill, when the postman loomed round the corner, over the snow … I wish you could have been there on the hill summit – the valley all white and hairy with trees below us, and grey with rocks – and just round us on our side the grey stone fences drawn in a network over the snow, all very clear in the sun. We ate the sweets and slithered downhill, very steep and tottering … at Ambergate my sister had sent a motor-car for us – so we were at Ripley in time for turkey and Christmas pudding”.

Remarkable to discover that the postman delivered on Christmas Day, and even more surprising that they must have walked at least seven miles to Ambergate – unless the trains were also running!

Later that winter, on February 9th, he again wrote to Katherine:

“But it is immensely cold – everything frozen solid – milk, mustard, everything …Wonderful it is to see the footmarks in the snow – beautiful ropes of rabbit prints, trailing away over the brows; heavy hare marks, a fox, so sharp and dainty … Pamela is lamenting because the eggs in the pantry have all frozen and burst. I have spent half an hour hacking ice out of the water tub – now I am going out”. (Pamela was his name for another sister).

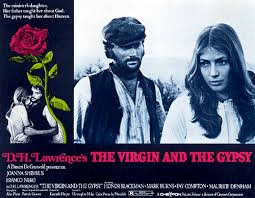

By spring the Lawrences had moved south, and were soon en route for Italy, which must have been a welcome relief after living above a frozen Via Gellia. But he never forgot this corner of Derbyshire, since he set his novella, The Virgin and the Gypsy in a village clearly based on Cromford, called Papplewick in the story:

“Further on, beyond where the road crosses the stream, were the big old stone cotton mills, once driven by water. The road curved uphill, into the bleak stone streets of the village”.

NB: Mountain Cottage can be seen from the road, on the right descending from Middleton to the Via Gellia. If walking take care as the road is quite narrow, busy, and there is no pavement.