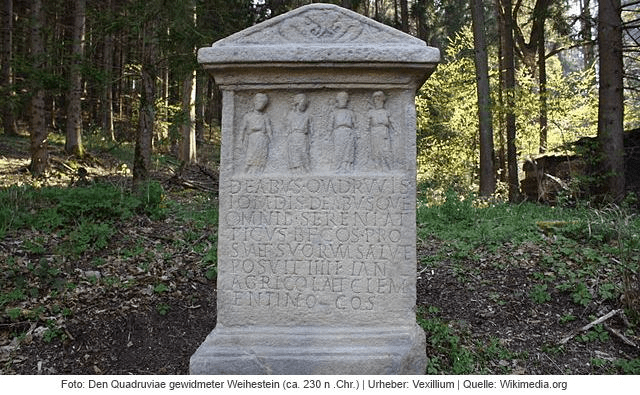

Altar to the Quadruviae in Germany

For at least two thousand years European roads were marked by shrines and sanctuaries, giving travelers the chance to rest, make offerings and pray for a safe journey. The Romans dedicated some to well-known gods such as Hercules and Mars, but they also had divinities specific to travel: Biviae at the meeting place of two roads, Triviae for three and Quadruviae for four, as in the example above, found in Germany. These junction divinities were all female, and give us some insight into the mindset of the ancient world. Even in medieval times in England a crossroads was seen as a place of significance, suitable for the burial of suicides (finally abolished by act of parliament in 1832).

Roadside scene (detail). Eighteenth century

The painting above, in the Thyssen Museum in Madrid, provides a rare glimpse of what may have been a common sight in the pre-industrial world: at a small stone shrine one man is on his knees, while another, on horseback, makes an offering. Yet in Catholic areas of Europe this tradition continued into the twentieth century, as described by DH Lawrence in his essay ‘The Crucifix across the Mountains’. In 1912 Lawrence and Frieda made an epic journey, mainly on foot, from Bavaria to Lake Garda in Italy. Lawrence was struck by the carved wooden crucifixes they found by the roadside:

Coming along the clear, open roads that lead to the mountains, one scarcely notices the crucifixes and the shrines … But gradually, one after another looming shadowily under their hoods, the crucifixes seem to create a new atmosphere over the whole of the countryside, a darkness, a weight in the air …

Derbyshire roads had their share of shrines, although little is known of pre-Christian examples. However, it is difficult to judge which of the surviving crosses were boundary markers and which were wayside crosses. At the reformation in the sixteenth century the crosses, usually dedicated to a saint, were generally destroyed as being Popish. However, a few survived, such as the cross at Wheston, which has the Madonna and Child on one face and the Crucifixion on the other. It is about 11 feet tall, but part of the shaft is more recent. Such crosses must have helped travelers navigate generally, but may also have been used to point the way to pilgrimage churches. One clue to the previous existence of a cross is the name ‘Cross Lane’, found in various locations in the county, such as just above Dethick. The topic is fully explored in Neville Sharpe’s ‘Crosses of the Peak District’.