Whatstandwell must be one of the more bizarre place names in Derbyshire, mispelt on some old maps as ‘Hotstandwell’. In fact it commemorates Walter (Wat) Stonewell, who lived near the bridge, built by John de Stepul in 1391, according to records from Darley Abbey. The bridge was rebuilt in the late eighteenth century, and widened more recently. Although the bridge today carries the north/south A6, it was originally constructed for east/west traffic, moving between Crich, Wirksworth and beyond. Building a bridge here would have been a major expense, and John may have paid for it as an act of charity. Clearly the original bridge must have been narrower and more basic, but such an early date suggests the importance of this river crossing, which would have been a ford previously.

On the east side of the bridge there are two main routes which converge on the river crossing. The main road (B5035) climbs steeply over the canal and up towards Crich. This was part of the Nottingham to Newhaven turnpike of 1759, which eased the gradient of the climb up to Crich by adding a loop above Chasecliff farm. The original track can still be followed, climbing directly up the hillside, with a stone causey still visible in places, as shown above. The other route has been obscured by the building of the canal and railway, but can still be followed by taking the Holloway road towards Robin Hood and then taking the first path on the right. This leads up through Duke’s Quarry, named after the owner, the Duke of Devonshire, and this track would have carried stone to either the trains or barges. However, the path is much older than either types of transport, and continues up through pleasant, semi-wooded fields to Wakebridge.

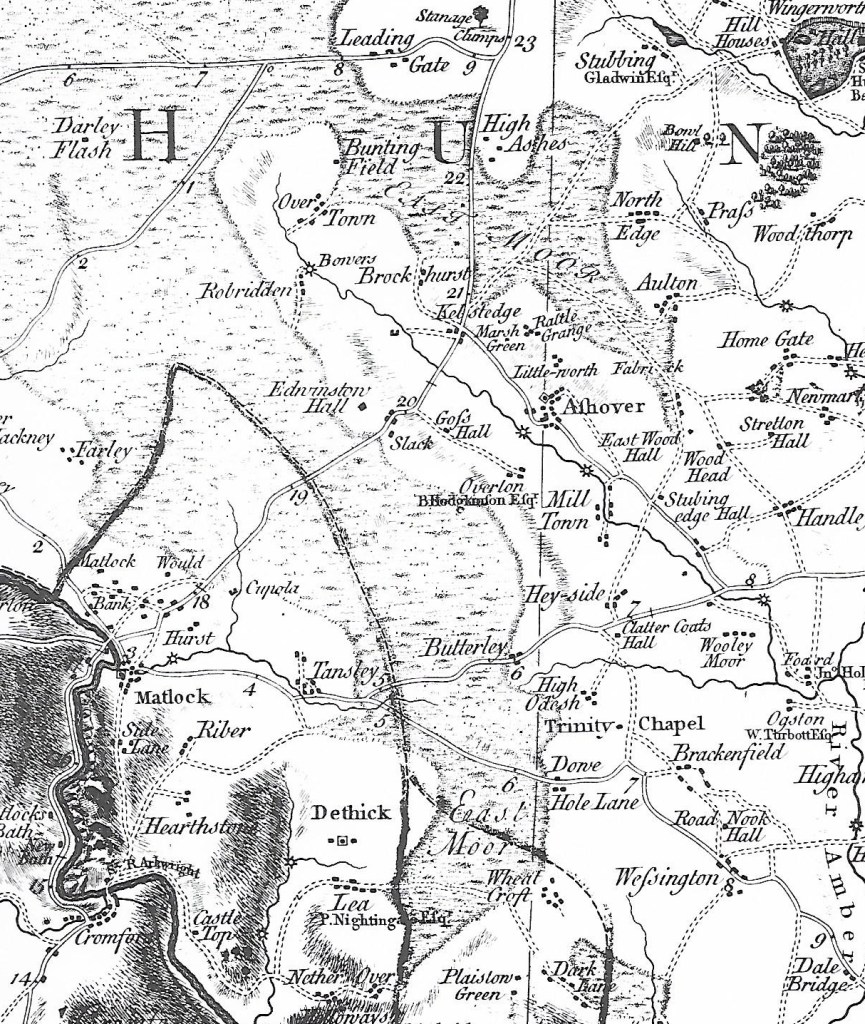

After crossing the Crich/Holloway road (currently closed) the track now runs to the left of Wakebridge Farm and climbs steadily to high ground at about 270 metres. As can be seen on the map, Shuckstone Cross in Shuckstone Field is the meeting point of at least five paths. Only the stone cross base now remains, but this is (possibly) marked with the destinations of the routes. The track from the bridge now continues northwards to meet the road, but can be walked to High Oredish and beyond that, Ashover. Although in practice it’s impossible to date routes such as these, the section from Wakebridge up to Shuckstone is exactly on the boundary of two of the historic Derbyshire hundreds, which suggest that it may have existed before the county was divided in the Saxon period.