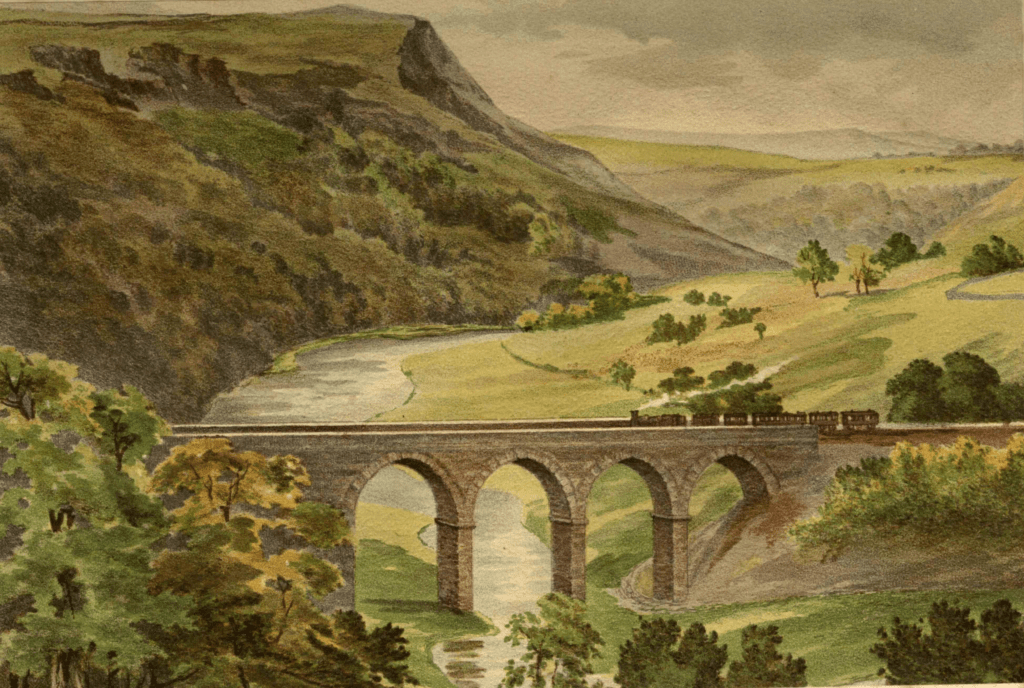

Fin Cop lies on the route of the Portway, about two kilometres north of Ashford in the Water. It is perched on a headland high above the sharp curve in the River Wye in Monsal Dale, and consists of a ditch and incomplete ramparts enclosing an area of about ten acres. Pennyunk Lane, which is believed to be a Celtic name, passes nearby, and is a section of the Portway whose route been somewhat modified by field enclosures. The question is – what was the purpose of the site?

The OS map marks the site as ‘settlement’, although it is often labelled ‘hillfort’. In fact it may have had several functions, as revealed by the extensive excavations which were carried out in 2009 and 2010 by the local history group supported by Archaeological Research Services. These reveal activity on the site going back to the Mesolithic – the time of hunter gatherers, when local chert was worked into tools. During the Bronze Age there were a number of barrow burials on site, and some kind of enclosure, possibly for corralling livestock. However, the idea of a permanent settlement seems unlikely, at nearly a thousand feet and far above a water source – much more probable that this was a ‘caravanserai’ on the Portway, being about ten miles from the next at Mam Tor, enclosing enough pasture for travellers’ animals to graze on.

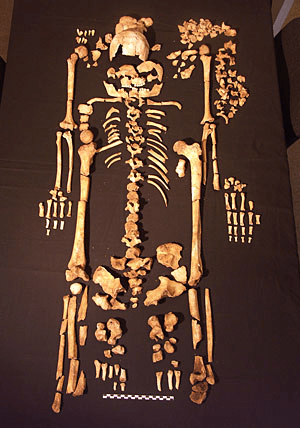

There seems to have been a change, possibly climatic, in the Peak District in the Iron Age, indicated by a reduced population. This theory is supported by the dramatic finds made by the excavation of 2010, which show that about 400 BCE the ramparts were hurriedly raised to a height of about three metres and a ditch dug alongside. In the excavated sections the skeletons of nine women and children were found, whose bodies appear to have been hurriedly thrown into the ditch before the walls were broken down. Given that only a fraction of the site was excavated, this suggests a massacre of possibly over a hundred people, and warfare on a serious scale. We will never know the full story of this fascinating place, but these recent finds give us a taste of one chapter in its long history.

Source: https://www.archaeologicalresearchservices.com/projects/site/index.html