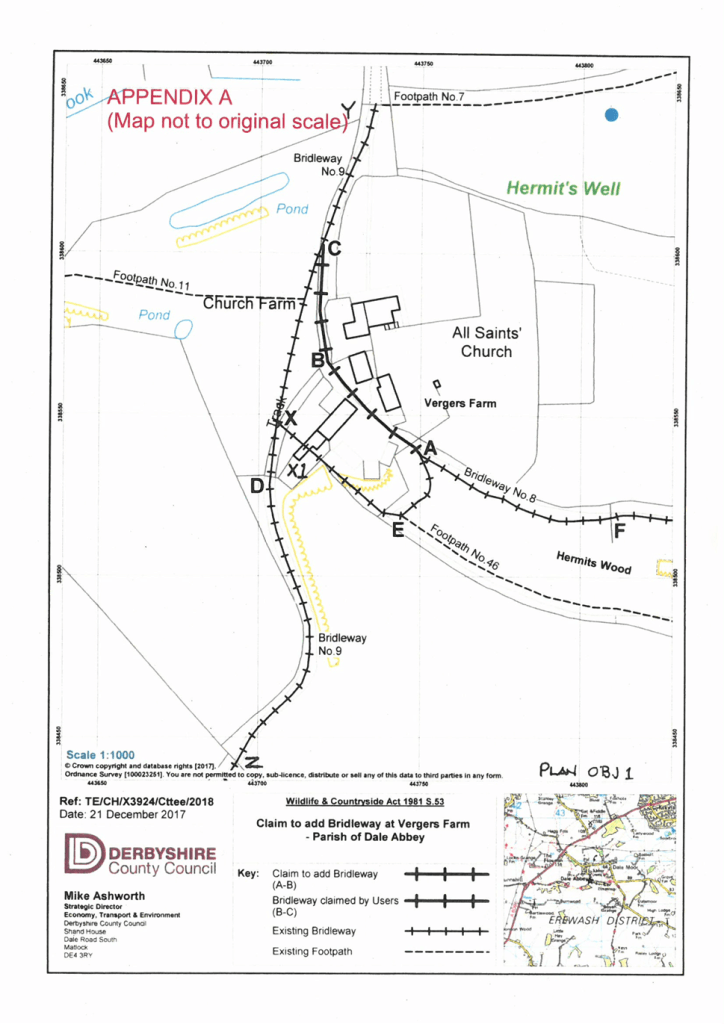

The importance of public rights of way – both footpaths and bridleways – in England is shown by the tremendous effort expended on settling disputes when these routes are challenged. A recent example is at Dale, near Ockbrook in the east of Derbyshire, where the Portway runs past the remains of Dale Abbey and the Hermit’s Cave. The ancient track leaves Hermit’s Wood, goes past the church and into the village, and this point has been the focus of the disagreement.

The owners of Verger’s Farm attempted to obstruct use of the route through their farmyard, claiming that an alternative route (E to X on map) should be used, although this involved a stiff climb. This led to an official inquiry opening in 2019, led by an inspector from Defra (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs), who was unable to carry out a site visit until 2021 due to the COVID pandemic. 23 people gave evidence in support of the long-standing existence of the bridleway through the yard, including members of the British Horse Society, a powerful lobby. Against these were 14 objectors, including the family of the farm. A mass of documentary evidence was also presented, including old photos and guidebooks to the district. The inspector, in her final decision in 2023, confirmed the validity of the original route of the bridleway on the strength of the historical evidence, leaving aside the personal statements.

This case illustrates the extraordinary passions that a right of way dispute can generate. The bridleway in question is only a few hundred metres long, but caused an argument involving dozens of people, the parish council, the county council (DCC) and Defra, which continued for over four years. Now that the way is officially waymarked, we should recognise their efforts by visiting the village; either walking from the Carpenters’ Arms in Dale village or taking the more ambitious route along field paths from the Royal Oak in Ockbrook.