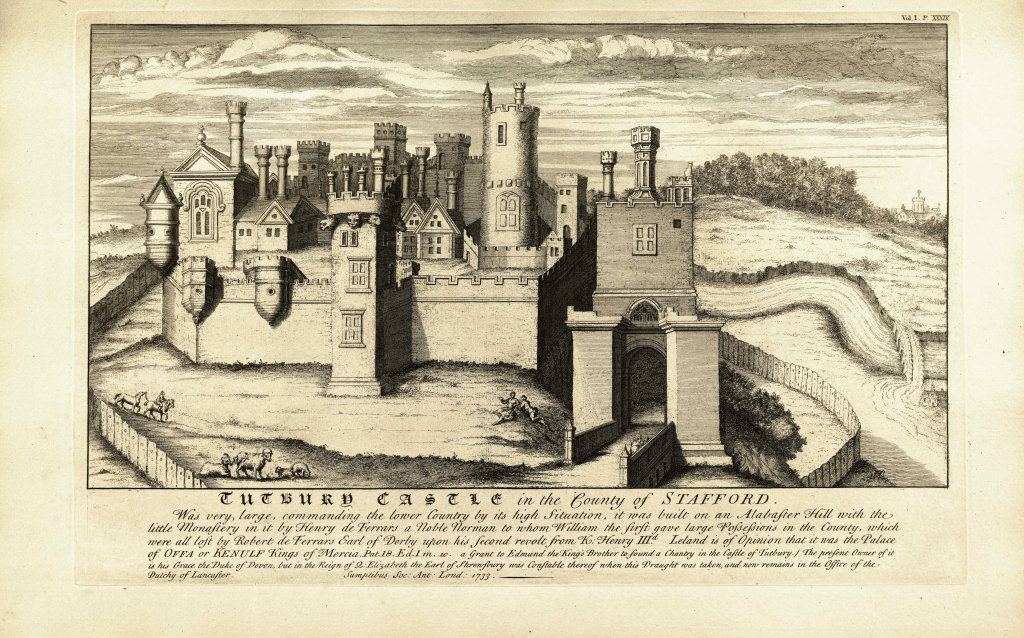

When Mary, Queen of Scots escaped from the rebellious Scottish lords in 1568 to find shelter in England, she could not have imagined that she would spend the next 18 years as a prisoner of her first cousin once removed, Queen Elizabeth. The Earl of Shrewsbury had the misfortune to be chosen as her jailer, and he found himself caught between Mary’s complaints about the quality of her prisons and Elizabeth’s (justified) suspicions of her cousin’s intentions. For most of her imprisonment she was kept at his houses and castles in Sheffield, Hardwick, Chatsworth, and Wingfield, with regular visits to Buxton, but initially she was confined in Tutbury Castle, just over the River Dove in Staffordshire.

Tutbury was seen as a suitable site, being sufficiently remote from both Scotland and the coast, and she arrived there in February 1569. She didn’t travel light, being accompanied by an entourage of 60, including doctors, ladies in waiting, chaplains and cooks, travelling from Yorkshire via Chesterfield and South Wingfield. You wonder how a small village was able to accommodate and feed so many, although it was common at the time to carry household items like sheets, pillows, and cooking utensils in carts from house to house. Shrewsbury was only allowed £45 a week to feed everyone, which added to his difficulties. In addition to complaining about the cold and the draughts, she also plotted with fellow Catholics to escape either to the Continent or Scotland, so he must have been relieved when he found reasons to cut back her followers and take her to the more convenient Chatsworth.

Mary was moved from place to place during her confinement, including Wingfield Manor, until the exposure of the Babington Plot led to her trial and execution at Fotheringay Castle in 1586. The stress of being her gaoler may have contributed to the breakdown of the marriage of Bess of Hardwick with the Earl of Shrewsbury. Today Mary is still often portrayed as a romantic heroine, but it was her scheming that led to the brutal killing of her fellow plotters. Coincidentally, both Tutbury Castle, managed by the Duchy of Lancaster, and Wingfield, run by English Heritage, are both currently closed to the public on rather flimsy excuses, despite their importance in the national narrative.