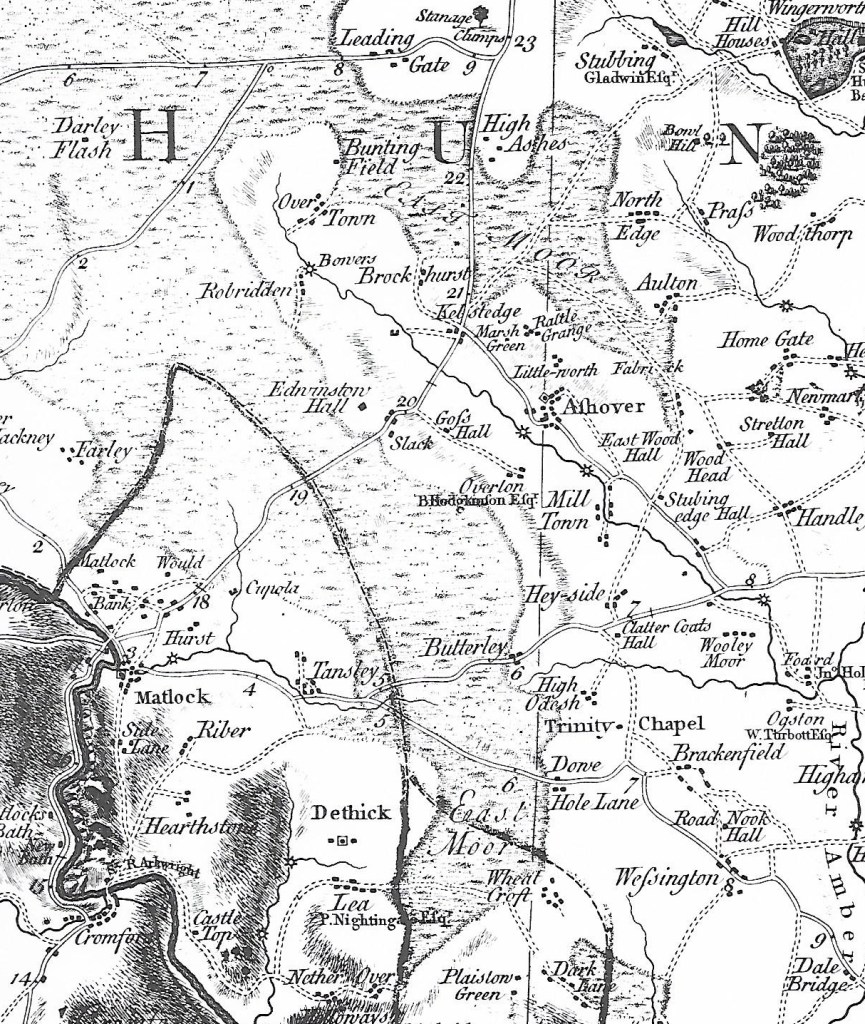

Part of Speed’s Derbyshire map of 1611: Wirksworth in centre.

It is a mystery of history that maps in the modern sense, as aids to travel, did not appear until the early eighteenth century. A few maps survive from the Roman and medieval periods, but they seem to have been rare and would not have helped the traveller. Presumably wayfarers simply had to ask the way. The first county maps of England, and probably the first in Europe, were produced by Christopher Saxton in the 1570s, and these were plagiarised by John Speed, whose 1611 Derbyshire map is shown above. This might have been of some use to travellers, although roads are not shown: the dotted lines are boundaries of hundreds. However his map does show rivers, some bridges (e.g. Belper bridge), and the fenced estates of the wealthy. Although it has the modern convention of north at the top it is still semi-pictorial in style, with little mountains and water mills. Note the erratic spelling: two versions of Wirksworth!

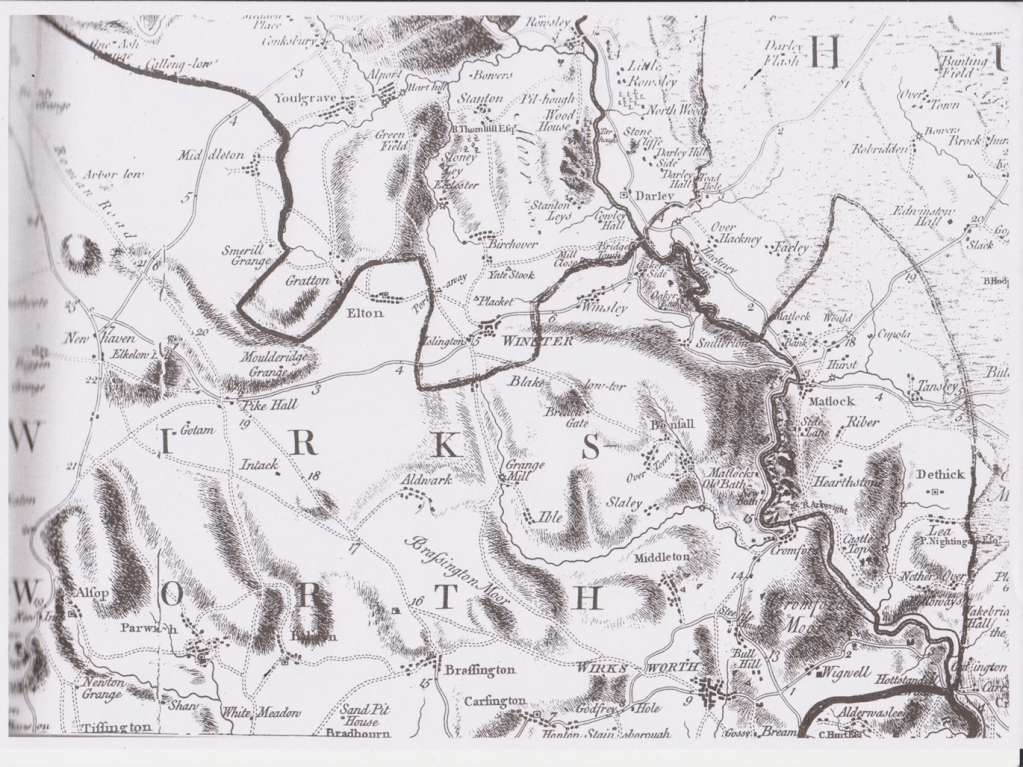

The first practical map for travellers was Ogilby’s strip map of 1675. As can be seen above, this maps the route from Derby (top right) to Manchester (bottom left), and shows villages, side roads, hills and some inns. This map is part of Britannia, a book of 100 major routes in the kingdom, at the innovative scale of one mile to an inch. However, this is the only Derbyshire road in the book, and it was not until 1767 that the whole county was surveyed for Peter Perez Burdett’s map (below). Although far from perfect, this is an invaluable reference for historians, depicting in detail the county’s villages, forests, and, for the first time, the main roads.

Burdett’s map of 1767 – the Derwent runs from top to bottom on right.

The map was revised in 1791 and so shows the turnpike roads (and mileages) as solid double lines. However, minor roads, lanes and paths are not marked. (The very thick black line is a hundred boundary). Upland is now shown by hatching, but it is obvious that the Via Gellia, west of Cromford, did not yet exist (or had not been recently surveyed). The names of some landowners are included, for instance Richard Arkwright at Cromford, and the maps were probably aimed at this class of customers, rather than ordinary travellers.

Ordnance Survey map of Youlgreave 1898: 25 inches = 1 mile

The first Ordnance Survey maps of Derbyshire, at a one inch to one mile scale, were not produced until 1840. Perhaps for the first time, accurate maps were available at a reasonable price. Later in the century larger scale maps were produced, such as the one above, which show every footpath, field and house, and so are a valuable resource for historians. Today we are so used to planning trips on cheap folding paper maps, or, increasingly map apps using GPS on our phones, that it’s easy to forget how recent these resources are. But perhaps the biggest mystery is how our ancestors moved around the country not only without maps, but without ever having seen a map in their lives?