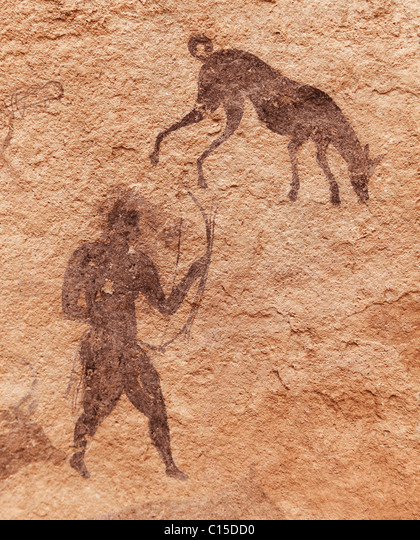

Dogs were the first animals to be domesticated, apparently during the last ice age, about 15 or 20,000 years ago. Hunters may have shared their kill with young wolves, who became camp followers and provided some services in return. Dogs could be trained to help the hunters by retrieving game, as well as guarding their campsites. Travellers soon found that dogs made useful companions on a trek, especially if they were herding animals such as cattle or sheep. As cities grew in the eighteenth century and the demand for fresh meat rose, drovers and their dogs walked the cows from the upland districts in the north and west to the butchers of Sheffield or Nottingham.

Perhaps even more significant was the domestication of the horse, thought to have occurred about 5,000 years ago, in the early Bronze Age, near the eastern borders of Europe. Evidence for this are the elements of horse harness such as bits and bridles found in grave burials around 2,000 BCE. For the next four thousand years horses provided the fastest travel on the planet, as well as weapons of war (cavalry and chariots) and transport of goods (either as packhorses or pulling carts). Over long distances a rider could average about four miles an hour, so about 30 miles was a good daily total for both rider and horse, with about seven hours in the saddle. It seems remarkable that just 200 years ago our entire economy was based on horse power, from agriculture to personal mobility to powering the first railways!

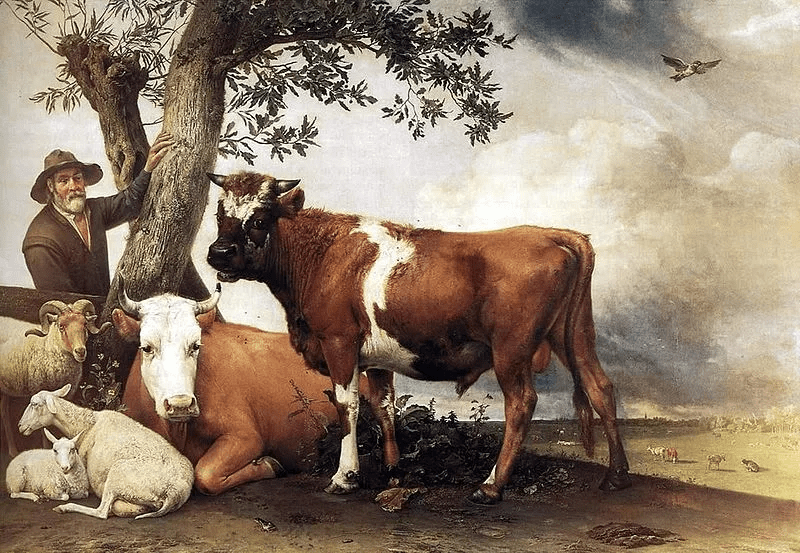

Today’s walkers in Derbyshire are likely to be concerned about crossing fields with cows grazing, especially if they have dogs with them. Although the number of deaths caused by stampeding animals is small, it is a real risk, and most hikers have had uncomfortable experiences, if not worse. Although likely to be an underestimate, the HSE keeps records of injuries from cattle, and between 2000 and 2020 98 people were killed by them: many more were presumably injured. Of these the majority (76) were farm workers, and the rest were walkers. The general consensus is that bullocks represent a greater danger than the odd bull, and that cows with calves should be given a particularly wide berth. Carrying a stick probably makes the walker feel better, and dogs should be let off their leads to escape quickly if a situation feel threatening.