Today’s tech tycoons play with their spacecraft, but 150 years ago a wealthy Victorian built his own railway in his garden at Duffield Bank, complete with several tunnels and six stations. Sir Arthur Heywood had inherited money and the baronetcy from his father, and as a gifted amateur engineer wanted to test his belief in narrow gauge (15 inch) railways. Of course the standard gauge of four feet eight and a half inches had long been adopted in Britain, but Heywood thought that there was a role for much narrower gauge railways on private estates.

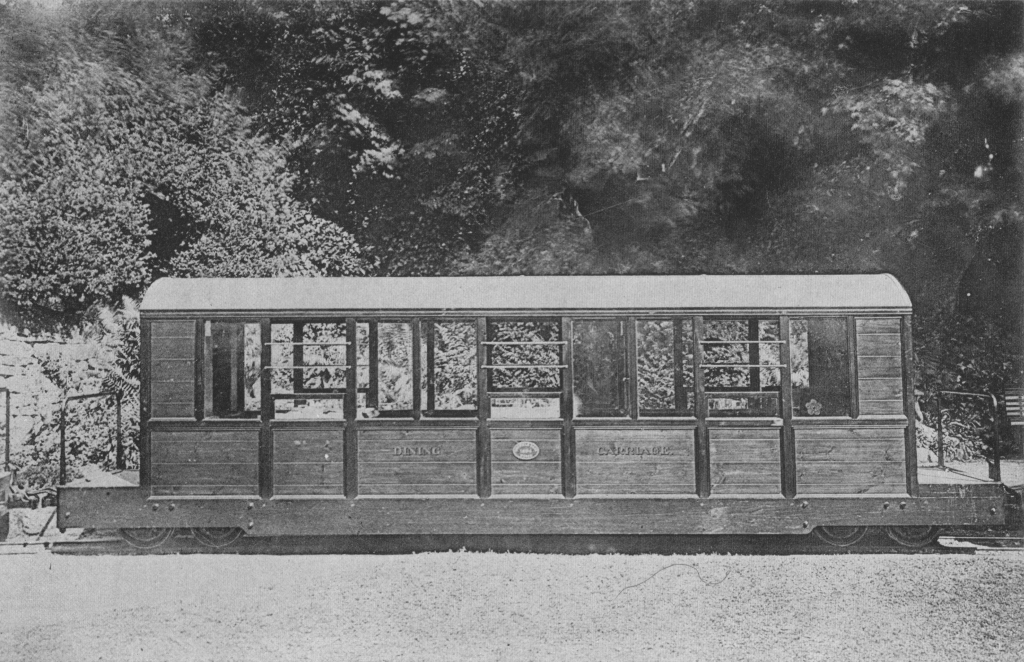

Despite being a mile long, Heywood’s railway had no regular passengers and was really built as a testbed for his engineering experiments – a rich man’s passion. However, as can be seen, open days were held for people from the Duffield area. Remarkably, the rolling stock – all built in Heywood’s own workshop – included a dining car with a stove and a sleeper car, probably only used by his children! Several steam engines were built on site: the earliest was little Effie, pictured above at top, but later models were 0-6-0 tank engines Ella and Muriel.

Rather sadly, despite all his efforts, there was little interest in building new lines on this gauge, the only taker was on the Eaton Hall estate in Cheshire, owned by the Duke of Westminster. Sir Arthur died in 1916 and his railway was broken up, with some equipment sold to other narrow gauge companies such as the Ravenglass and Eskdale line. Clearly Heywood underestimated the advantages of road travel, as did various attempts to operate light railways for passengers in the district. The Ashover and Clay Cross Railway was a two foot gauge line that ran a passenger service from 1924 to 1934, while the Leek and Manifold Railway was a two foot six inch line that operated from 1904 to 1934. Obviously, by the mid 30s competition from buses and private cars was killing off these marginal railways.

Source: Duffield Bank and Eaton Railways, Clayton Howard