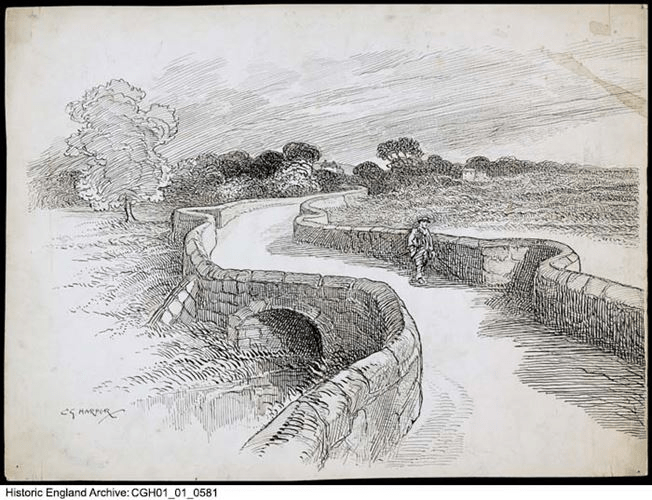

The causeway in the old days

Swarkeston Bridge was once the only crossing of the Trent between Burton and Nottingham, carrying traffic on the north-south route through the Midlands to Derby and beyond. At this point the river flows through low-lying meadows which flood regularly, and so the road is carried across these on a causeway about three quarters of a mile long. Most of this is medieval, although the actual river bridge was rebuilt in 1801. The whole structure is a clear illustration of the importance of river crossings in the past, and the resources that were devoted to constructing them. In this case, the legend tells of two unmarried sisters who lived on the north bank, and during a flood watched helplessly as their lovers tried to cross the torrent on horseback, before being swept away. As a result they spent all their resources on building the causeway, thereby impoverishing themselves.

Less peaceful today

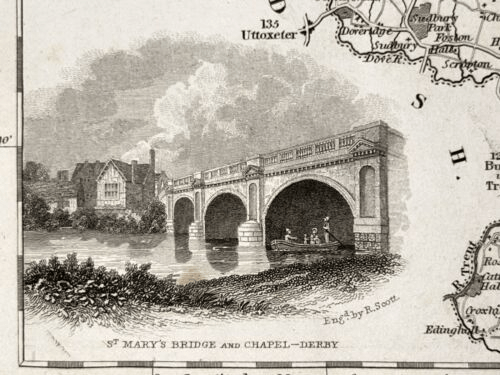

Even when wealthy donors funded a bridge, maintenance was a constant issue. The Church seems to have been responsible for most bridges, and consecrated a body of men called ‘bridge hermits’, who were given an adjacent chapel to live in and were responsible for collecting tolls to pay for repairs. There are records, for example, of the Bishop of Ely in 1493 appointing a Robert Mitchell to the post and giving him a special outfit to wear. Although the bridge chapel at Swarkeston has disappeared there was also a chapel of St James by Chesterfield Bridge, while ruins of a chapel remain by Cromford Bridge. The best surviving example is by St Mary’s Bridge in Derby, which until the nineteenth century was the only crossing of the Derwent in the town.

Bridge and chapel in 1835

A list of the tolls charged (pontage was the term) for Swarkestone Bridge in 1275 is evidence of the extraordinary variety of goods traded in the region in medieval times. Tolls ranged from a farthing to 6 pence a load, although pedestrians were apparently not charged. This is a short extract from the list, but one wonders how the bridge hermit could assess all these tolls:

- Any load of grass, hay, brush or brushwood – a farthing

- Any horse, mare, ox or cow – a farthing

- Any skin of horse, mare ox or cow- a farthing

- Any pipe of wine – a penny

- 5 flitches of bacon, salted or dried – a farthing

- A centena of skins of lambs, goats, hares, squirrels, foxes or cats – a halfpenny

- Every quarter of salt – a farthing

- Every pack saddle load of cloth – three pence

- Every sumpter load of sea fish – a farthing

- Every load of brushwood or charcoal – a farthing

- Every burden of ale – a farthing