Today the image of a hermit is usually a scruffy-looking character living in a remote hovel. But although the route of the Derbyshire Portway is marked by several such hermitages in caves, the term was also used for men who were effectively toll collectors on key bridges. Such bridges were a common good, but expensive to build and maintain, especially on the major rivers of Derwent and Trent, and the church played a major role in their maintenance. A good example is St Mary’s bridge in Derby, whose hermit in 1488 was John Senton, a married man who (unusually) shared his duties with his wife. He had the job of guarding the many votive offerings given by locals, as well as collecting tolls from travellers. The right to collect tolls at bridges was known as ‘pontage’, and might be granted by the king or a bishop, usually for three years.

Today the chapel has quite an austere interior, but in the medieval period it would have been decorated with offerings, such as (spelling modernised):

One coat of crimson velvet, decorated with gold, covered in silver coins

A crown of silver and gold

A great brooch of silver and gilt with a stone in it

A crucifix of silver and gold

One pair of coral beads

One pair of black jet beads

(Taken from the inventory of 1488)

Notably, most of the benefactors were women, and they were possibly members of a female guild dedicated to maintaining the bridge.

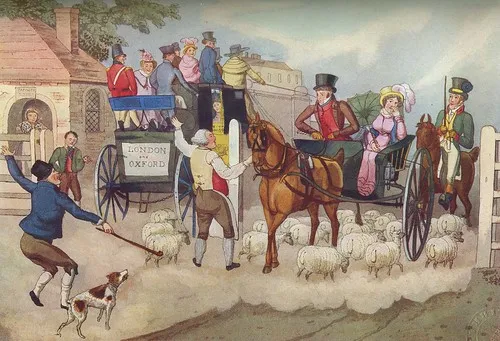

Other Derbyshire bridges charging tolls included Cromford, Chesterfield and, notably, Swarkeston, which had to face repeated battering from the River Trent in flood. The list of tolls here gives a graphic picture of the variety of goods on the roads in the high Middle Ages, and the presence of two items imported from Spain indicates the extent of trading networks at this time:

Cask of wine 2d

Skins of lambs, goats, hares or foxes 1/4d

Pack saddle load of cloth 3d

Bale Cordova (i.e. Cordoban leather) 3d

Brushwood 1/4d

Flitches of bacon 1/4d

Source: C. Kerry, Hermits, Fords and Bridge-chapels, The Derbyshire Archaeological Journal, 1892, Vol.14 pp. 54-71