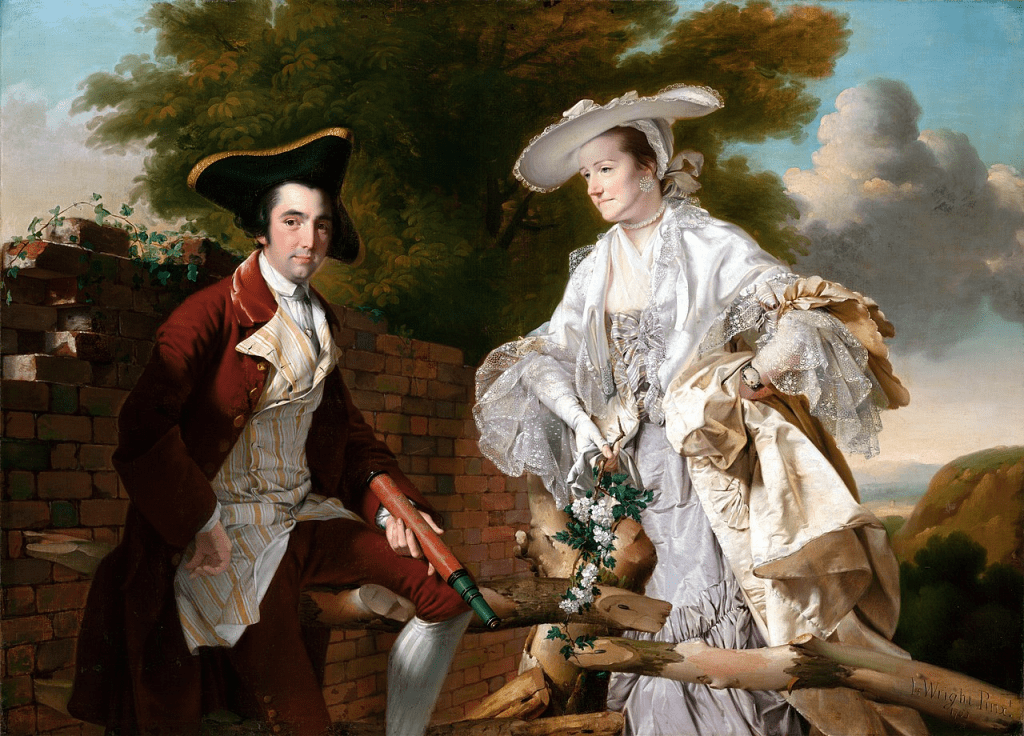

Peter and Hannah

Peter Perez Burdett (c.1734-1793) is a fascinating example of an eighteenth-century artist, surveyor, amateur scientist and … serial debtor! His map of Derbyshire (1767) is the first accurate survey of the county, at the scale of an inch to a mile, and is invaluable to local historians. He was a friend of the painter Joseph Wright, whose portrait of Peter and his wife Hannah (1765) shows them al fresco, as if posing on their country estate. Apparently she was a widow, somewhat older than Peter, and the marriage may have helped him raise capital for his mapping project. He is holding his surveying telescope, while she appears most unsuitably dressed for a country ramble! (Wright was a master of drapery). This double portrait can now be seen at the Czech National Gallery in Prague.

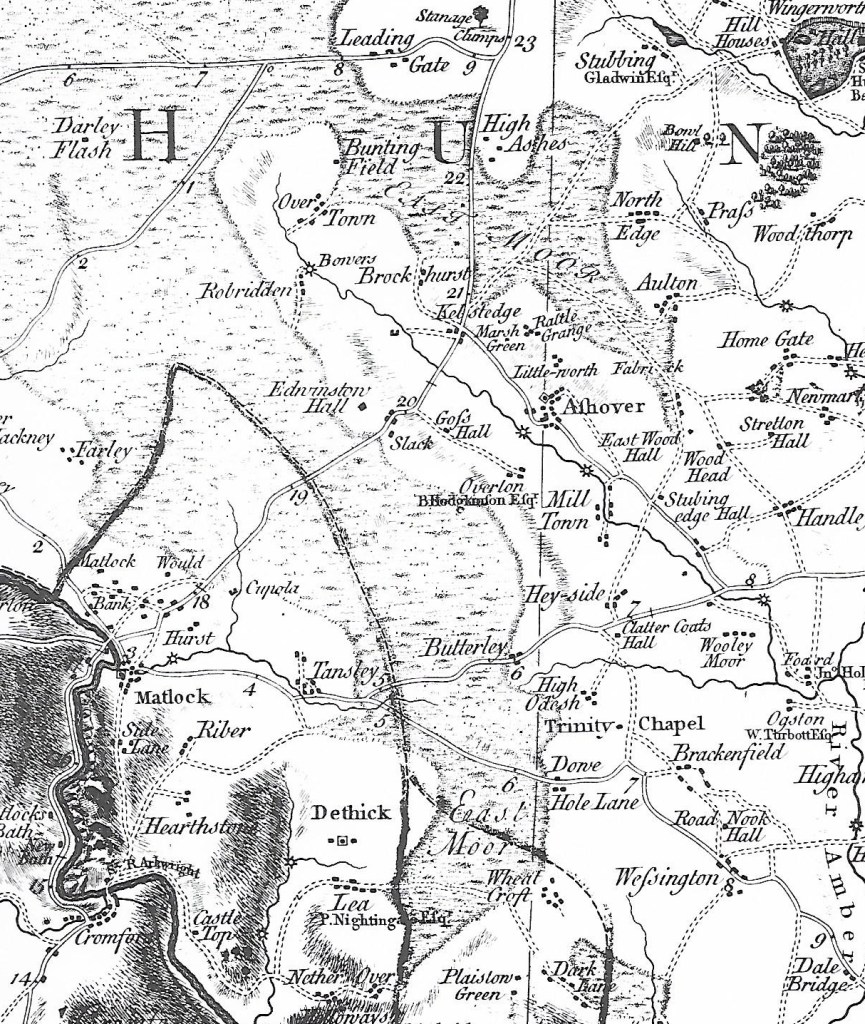

Plan of Derby from Burdett’s map of 1767

Burdett appears in several of Wright’s paintings, notably as the figure making notes on the left in Wright’s masterpiece, A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery (see below). But despite their friendship and his map-making achievements, Burdett chose to move to Liverpool in 1768, possibly to seek a new range of clients, but certainly to evade his creditors. There he surveyed the Liverpool – Leeds canal, and was also involved in the development of the new technique of making aquatints in 1774, producing several himself, and thus demonstrating his versatility.

Burdett makes notes

However, Burdett seems to have been again less proficient at managing his finances, since in 1774 he had to flee to Baden, in modern Germany, to escape his debtors. Leaving Hannah behind he, curiously, took their joint portrait with him! In Baden he found a patron in the Grand Duke, and also found a new wife, Friederike Kotkowski, who he married in 1787 at the age of 53. They had a daughter, Anna, who married into the local aristocracy. Peter was clearly successful in his new milieu, surveying schemes for the Grand Duke until dying in 1793 at the age of 59. His story illustrates the extraordinary versatility of many men (and some women) in this period of rapid social change and scientific advances.