Just north of the Matlock-Alfreton road (A615), the hamlet of Mathersgrave commemorates both a family tragedy and a medieval mindset. Set in the retaining wall to a cottage garden is a block of stone inscribed ‘SM 1643’ and nearby is a guidestoop with three inscriptions: ‘Matlack (sic) Road’, ‘Bakewell Roade’ and ‘Alfreton Road 1730’. The presence of the guidestoop shows that this was a significant crossroads in the early eighteenth century; building the turnpike bypassed the junction.

Christian teaching in the Middle Ages insisted that suicide was a serious sin, and this was reinforced by English law which viewed it as a crime, punishable by the forfeit of property to the crown. Suicides were denied burial in consecrated churchyards, and thereby lost their chance of going to heaven. Instead they were buried at crossroads, where it was thought their spirits would be unable to choose the right route back to the land of the living, and so be unable to plague their kin. To make doubly sure, a stake might be driven through the heart of the sinner to further immobilise them. Incredibly, the last case of a crossroads burial was in 1823, while suicide remained a crime until 1961.

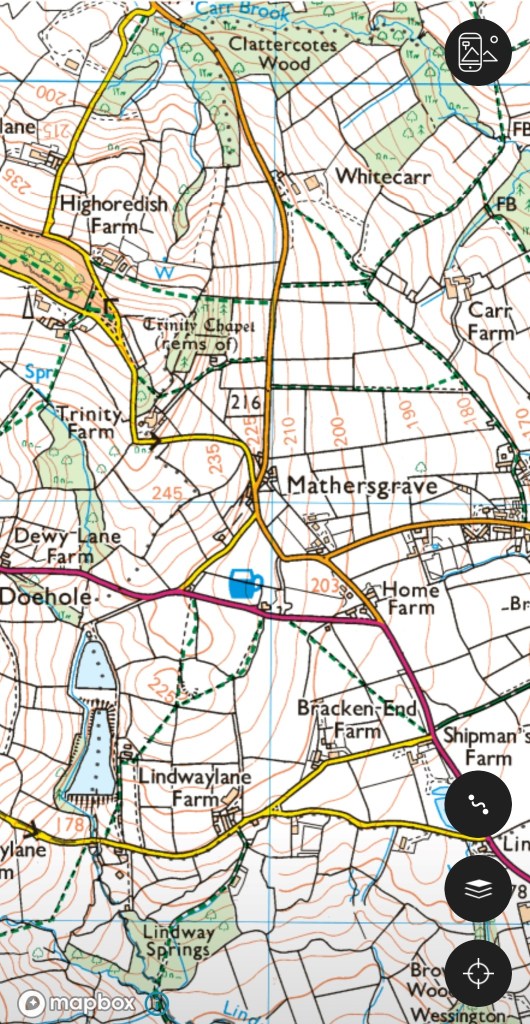

Apparently SM was Samuel Mather, a local man who had fathered an illegitimate daughter, and social condemnation forced him to kill himself, and possibly kill his wife also. (Details of the story are vague). This happened in 1716, so the date on the marker stone is wrong. This occurred well before the Matlock-Alfreton turnpike was constructed, and further evidence of the shift in road pattern is the romantic nearby ruin of Trinity Chapel. Half a mile to the north, (see map above), this was in use before Brackenfield Church was opened in 1857, but is now quite deserted. In the past this must have stood on a busy lane, but today is only reached by footpath.