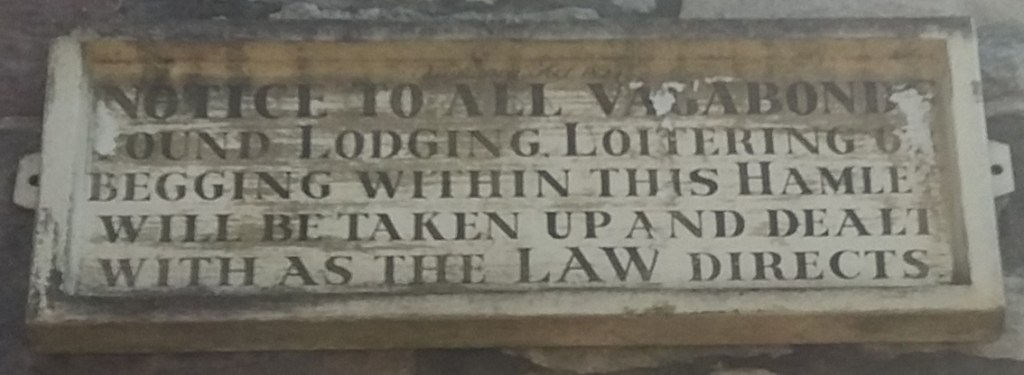

Travellers by road and rail have been confronted by baffling or unhelpful signs for many years. The example above, warning vagabonds who loiter in Alport that they may be ‘taken up’, supposes that such vagabonds can read, which seems unlikely in the (?) early nineteenth century. The modern equivalent must be the numerous ROAD CLOSED signs currently found all over the county, which either don’t specify which road is closed, or else mean the road is only half closed.

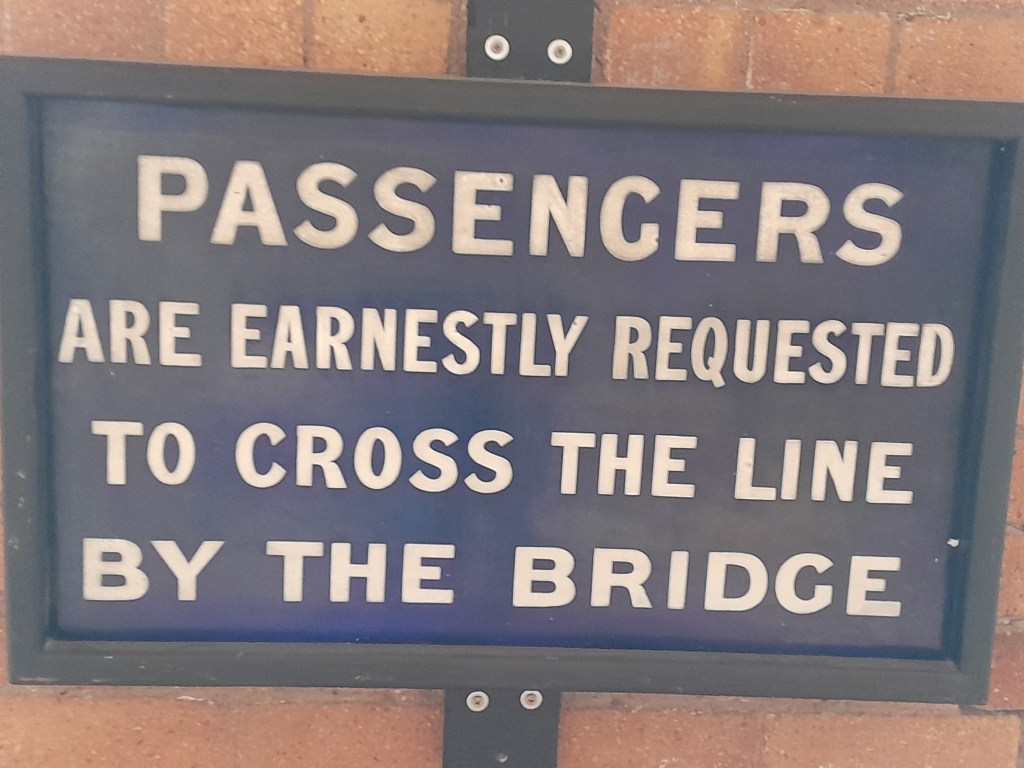

The tone of the wording on signs can vary from the curt (above) to the ultra-polite (below). To ‘request’ a pattern of behaviour is genteel, but to ‘earnestly request’ makes it impossible not to comply . Both these examples can be seen at Derby’s Museum of Making, which has a wonderful collection of these signs from the Midland Railway.

Other station signs are a reminder of the heyday of railway travel, when waiting rooms were not only provided for the different classes of ticket holders, but also separately for men and women. So presumably a large station like Derby would have had four different waiting rooms!

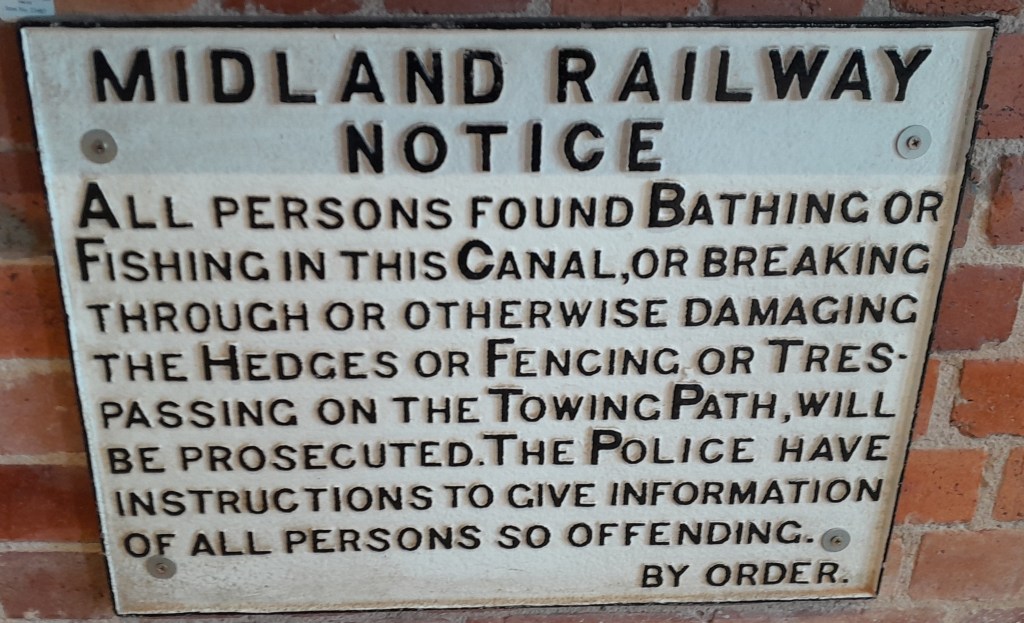

The railway authorities seem to have had a weakness for verbose and very formal inscriptions. Trespassers on the canal towpath or anyone having a dip in the canal was unlikely to bother to read all of this threat (below), while anyone about to spit might not understand language like ‘abstain’ or ‘objectionable’ – though the threat of TB was very real before the arrival of antibiotics.

More earnest requests

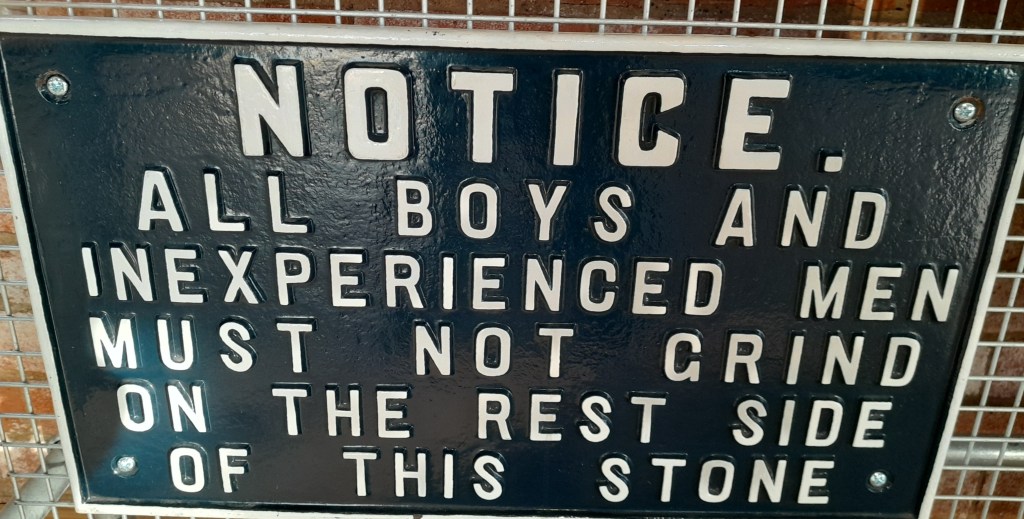

My favourite sign, which is quite unintelligible, must have been displayed in a works context, so presumably would be understood by those who worked there (below). There must have been hundreds of signs like these around the railway network, all nicely produced in iron or steel. It would be interesting to know if the railway company made them in-house, or if they used a specialist supplier.

However, the prize for the daftest sign of all must go to a modern effort, found on the A6 at Ambergate. What, you wonder, would be enforced by a helicopter? The speed limit? You imagine a ‘copter chasing a BMW down the road, and swooping onto the roof of the offending vehicle. This has all the making of a new reality TV programme …