‘But it’s real England – the hard pith of England’, Lawrence wrote to Rolf Gardiner in 1926. He was referring to the hill country of the Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire border, near his birthplace at Eastwood, going on to offer to ‘walk it with you one day’. Various walks described in Sons and Lovers explore this area. One of the most arduous took place on an Easter Monday, when, aged nineteen, Paul (i.e. Lawrence) organised a walking party of family and friends, including his sister and Miriam.

We also have his sister Ada’s description of the real walk, which took place in 1905, and which she recorded in her Early Life of D.H. Lawrence. Parts of her account show an interesting discrepancy with his fictional version. For instance, Sons and Lovers portrays the young people as feeling rather nervous when they enter Alfreton Church, but according to Ada they held a mock service:

He said we must sing a hymn or two, and threatened awful punishments if anyone laughed or treated the occasion lightly. I played the organ and we sang. After the boys had explored the belfry we set off for Wingfield.

It is not difficult to follow their route today, starting from Alfreton station. It is a modern, utilitarian structure, but is on a busy main line and offers direct trains to Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield, Norwich and Nottingham. The service between here and Paul’s starting point, Langley Mill (fictionally Sethley Bridge), still runs today.

It was great excitement to Miriam to catch a train at Sethley Bridge, amid all the bustle of the Bank Holiday crowd. They left the train at Alfreton.

The station is at the eastern edge of Alfreton, and it’s quite a long trek up Mansfield Road to the High Street. To the north of this route was the location of Alfreton Colliery, closed in 1967, and short terraces of what must have been miners’ houses lead downhill towards its site. On one corner is the Station Hotel, a bulky redbrick structure which was probably serving miners as Paul’s party passed by.

Paul was interested in the street and in the colliers with their dogs. Here was a new race of miners.

There are no details given of how the party went from here to Wingfield Manor, but the obvious route is to take the stone-flagged alley to the corner of the churchyard and then follow the green lane westwards. By the church the view of the hills, with Crich church spire and Crich Stand so clearly visible, shows that Paul really had no need of a map.

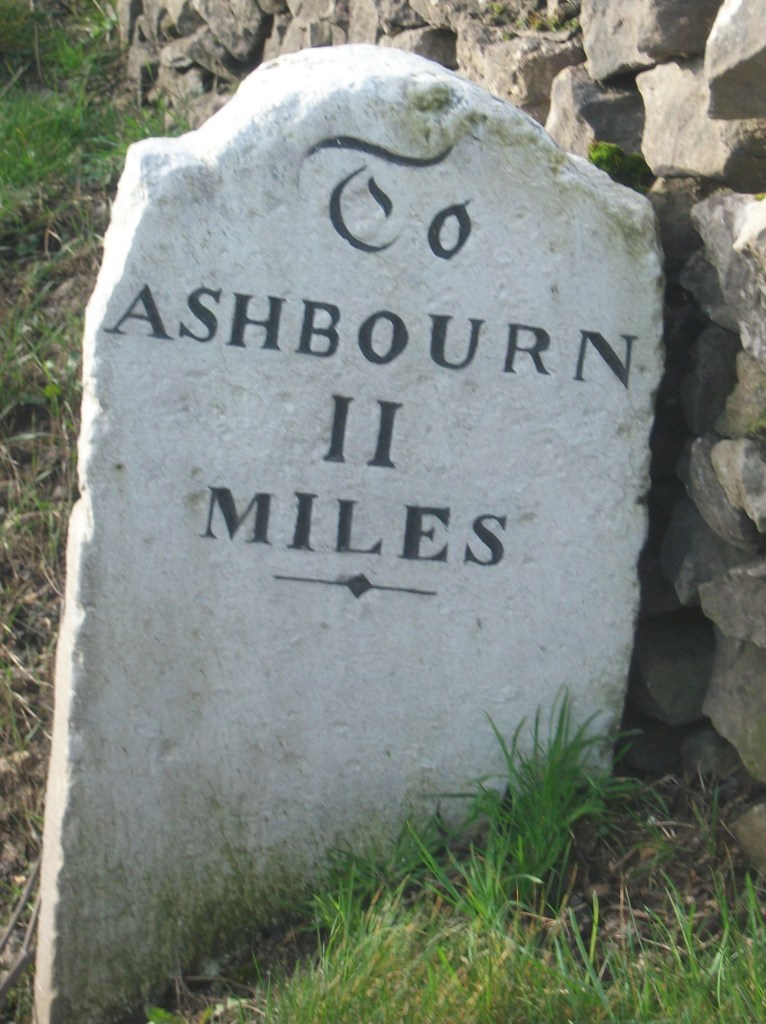

The green lane dwindles to a field path, but the route is clear, and after about a mile’s walk through deserted pasture you come out at the hamlet of Oakerthorpe, nearly opposite the impressive white bulk of the Peacock, an old coaching inn. This was the junction of two turnpike roads, one of which, running north, followed Ryknild Street, the old Roman road from Derby to Chesterfield.

The footpath continues heading west, beside the new houses, and then crosses the Midland Mainline on a wide wooden bridge. There’s a splendid view of the Amber valley from here, with South Wingfield church in the foreground and Wingfield Manor in the hazy distance. It’s a short walk down to the narrow river and then into the churchyard, frequently flooded and even more remote from the settlement than the one at Alfreton. Why, in the thirteenth century, was this damp spot chosen for a church, when the bulk of the village was on higher ground and nearly a mile distant?

South Wingfield is a village without a centre; everything, including the Manor, seems to be on the periphery. Wingfield Manor was apparently the focus of Paul’s expedition, with over a page devoted to a description of the ruins:

It was past midday when they climbed the steep path to the manor. All things shone softly in the sun, which was wonderfully warm and enlivening. … The young folk were in raptures. They went in trepidation, almost afraid that the delight of exploring this ruin might be denied them.

They were lucky not to make this visit today, since public access to Wingfield Manor has for years been limited to a few hours each month, for pre-booked parties only. This extraordinary restriction on access by the custodian, English Heritage, to one of the most important monuments in the East Midlands, which had been open to the public for over a century, has never been properly explained. Built by Ralph Cromwell in the 1440s, and used by the Earl of Shrewsbury to imprison Mary Queen of Scots in the sixteenth century, it is both highly picturesque and historically important. Despite this, it is now effectively out of bounds to the public, who will be denied the pleasures felt by Paul and Miriam:

Round the broken top of the tower the ivy bushed out, old and handsome. Also, there were a few chill gillivers, in pale cold bud. … The tower seemed to rock in the wind. They looked over miles and miles of wooded country, and country with gleams of pasture.

Fortunately there is a public footpath which runs around the back of the Manor and allows you to get fairly close to the buildings. It was here that the initial physical contact between Paul and Miriam is described:

She held her fingers very still among the strings of the bag, his fingers touching; and the place was golden as a vision.

The path comes out on a narrow road, Park Lane, which I followed uphill to Park Head. Paul’s exact route into Crich is uncertain, but there are clear field paths from here. Unsurprisingly, his party was now ‘straggling’, like the village itself:

At last they came into the straggling grey village of Crich. Beyond the village was the famous Crich Stand that Paul could see from the garden at home.

But this was not the same Stand that we see today, which was built as a war memorial to the Sherwood Foresters in 1923. At the turn of the century a shorter tower stood on the site, which had been built in the mid-nineteenth century but had become derelict by the time of Paul’s visit. However, at a height of nearly 1,000 feet, and on the edge of the Pennines, the view was and is magnificent: ‘They saw the hills of Derbyshire fall into the monotony of the Midlands that swept away south.’

The view of the Stand from Paul’s house at Eastwood has been mentioned before in the novel, and to some extent it represents for him the wider world, outside the mundane surroundings of his birthplace, in the same way that the Manor represents history and pageantry. In a perhaps related way, the name Crich, which suggested the literal horizon of Lawrence’s view throughout boyhood, was later used by him for the mine-owning family in Women in Love. From here the walk went downhill, metaphorically as well as literally:

They went on, miles and miles, to Whatstandwell. All the food was eaten, everybody was hungry, and there was very little money to get home with.

Ada Lawrence provided more detail of this section of the walk in her memoir. Apparently they continued on to Holloway, and then back to Whatstandwell, possibly by the canal tow path. On the first part of this route the view over the Derwent valley is spectacular, stretching from the towers of Riber Castle in the north to Alderwasley Hall and Alport Height further south. Arriving in Whatstandwell:

They managed to procure a loaf and a currant loaf, which they hacked into pieces with shut-knives, and ate sitting on the wall near the bridge, watching the bright Derwent rushing by, and the brakes from Matlock pulling up at the inn.

The Derwent river, the wall and the inn (now The Family Tree) are all still there, but it would now be difficult to buy any bread in the village as the last shop closed many years ago. The ‘brakes’ would have been horse-drawn carriages used for short outings, since this village was a recognised holiday spot, offering tea gardens with views of the valley.

The final leg of their walk was to Ambergate Station to get the train home, about two miles from Whatstandwell Bridge. At that time it would have been possible to walk along the road, now the busy A6, but today the tow path of the Cromford Canal offers a more peaceful alternative. The station at Ambergate would then have been much busier than the present unmanned halt; a hundred years ago it was one of the very few triangular stations in the country, and offered services to Nottingham, Derby, Sheffield and Manchester.

Paul was now pale with weariness. … Miriam understood, and kept close to him, and he left himself in her hands.

Their itinerary gives an interesting insight into levels of fitness then. The distance from Alfreton to Ambergate via Holloway is at least twelve miles, depending on route, but in addition they would all have had to walk to the station at Langley Mill (about two miles each way), and Miriam and her brother Geoffrey perhaps two more miles to their farm. So the minimum length of the walk was about sixteen miles – not exceptional, but quite impressive.