It’s hard to escape from Robin Hood in the north Midlands, with pubs bearing his name spread out over the region, from Macclesfield to Stoke and Sheffield to Nottingham. There are also Robin Hood wells, hamlets, fish and chip shops and the rock outcrop west of Winster, Robin Hood’s Stride. Clearly, the legendary figure has long had popular appeal, although in the case of the Stride the name must have been humorous, since the twin ‘towers’ are many yards apart.

The Stride provides an excellent natural landmark, visible for miles around, handily for travellers on the Portway, which runs between the Stride and Cratcliff Rocks. Before the days of maps people must have memorized a series of landmarks to avoid getting lost: perhaps certain trees, river crossings or rocks like this. But the Stride seems to have been at the junction of several routes, not just the roughly north-south line of the Portway, but also an east-west track.

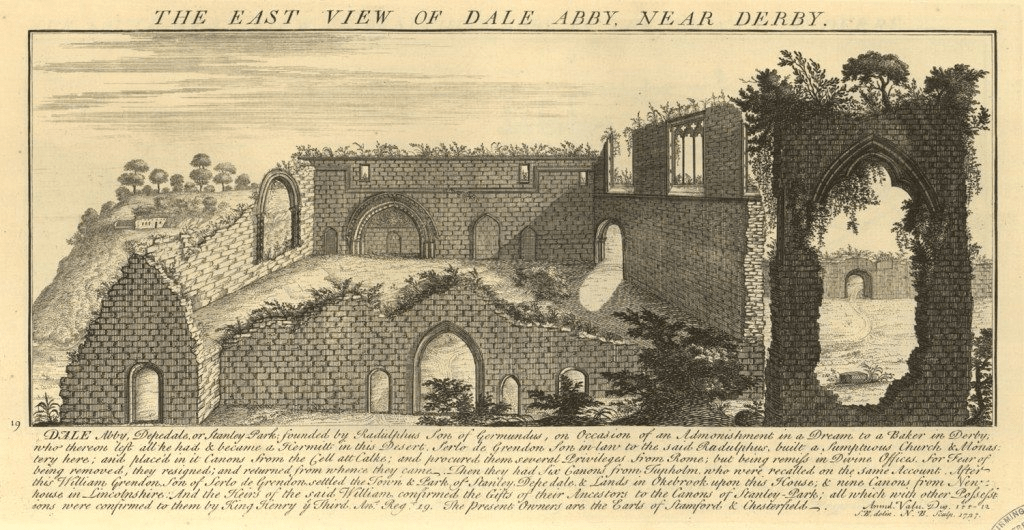

This very scenic walk can be followed on public footpaths, starting from the layby below Cratcliff Rocks on the B5056. 100 yards north a footpath climbs the sharp slope, and then joins a track heading east and following the contour line. Go past a ruined stone barn and continue along the top of Birchover Wood. At Uppertown the path becomes a track; follow along Clough Lane and Oldfield Lane till you reach a road and then turn right into Darley Bridge village. Turn left on the main road, cross the bridge, and just to the right of the Square and Compass pub take the field path over the water meadows. The importance of the river crossing is shown by the position of this Robinson’s pub – it has been regularly flooded but stoically continues to provide refreshment for travellers. This probable packhorse route continues past the DFS showrooms and up into Two Dales, where it follows an ancient way known as Back Lane, heading for Darley Flash and (probably) Chesterfield.