Just how old are the ‘old roads’? How were the first roads developed?

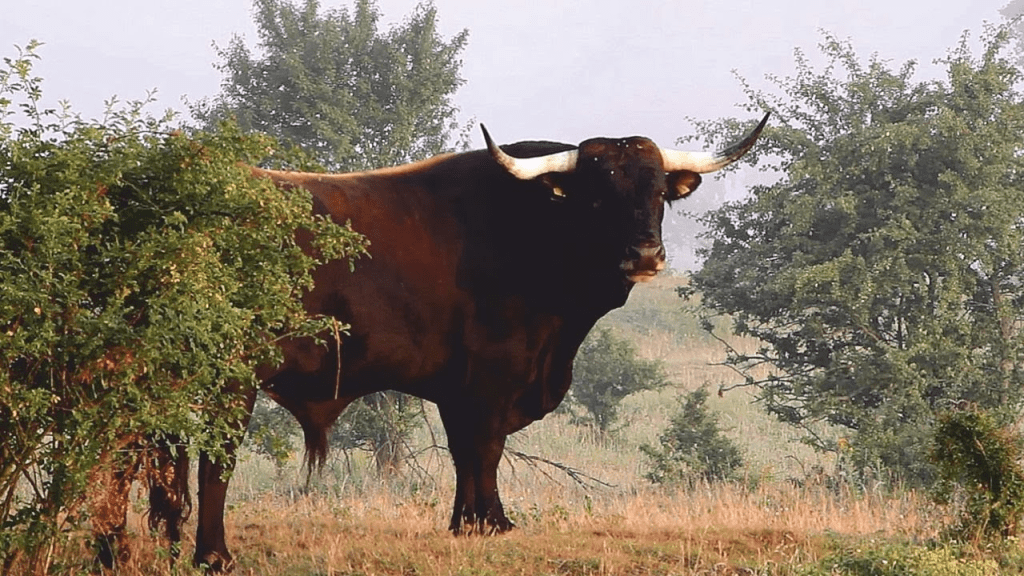

These questions are difficult to answer, but worth a try! The last ice age ended about 10,000 years ago, and the landscape of Britain must have gradually become more wooded as temperatures rose. Mammals would have arrived via the land bridge to the continent, including large beasts such as aurochs (early cattle), horses, deer and boar. These creatures are mainly herd animals, and would have travelled with the seasons, moving north in spring looking for fresh pasture and water, then south in autumn.

A herd of any large mammals would follow the easiest routes, avoiding the choking, dense growth in river valleys, and in doing so created channels of movement along the high ground. Their progress would hinder plant growth and so keep these routes open. They could drink from streams, but kept river crossings to a minimum, due to the risk of autumn floods. So when the first paleolithic (Old Stone Age) nomadic people arrived they must have followed these herds, both for the chance of making a kill and also because a proto-road offered the easiest route.

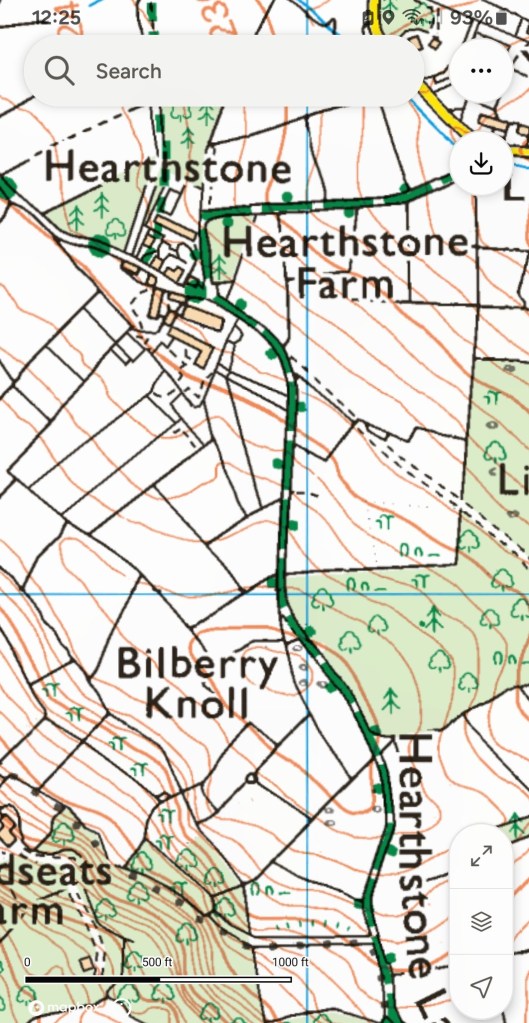

The very rare cave art found at Cresswell Crags, on the north east Derbyshire border, portrays deer, elk, wolves, hyenas and bears, clearly suggesting that Stone Age man had a close relationship with these creatures. Today many of their prehistoric ridgeway routes are still in use, notably many sections of the Derbyshire Portway, the lane from Belper Lane End to Bolehill, the A61 from Higham to Clay Cross, and dozens more.