How long have inns offered roadside refreshment to travellers? Not an easy question to answer, since many claim to be the ‘Oldest Pub in England’ or something similar. Nottingham has at least two claimants, The Trip to Jerusalem and The Bell, while in Derbyshire the Holly Bush at Makeney has clearly served a few pints over the centuries. The pilgrims in ‘The Canterbury Tales’, written in the late fourteenth century, stayed at the Tabard Inn in Southwark, so clearly inns were part of medieval travel.

However, the early eighteenth century saw a significant growth in travel, due to road improvement by the turnpike trusts and the invention of coaches with steel springs, cutting journey times and making travelling a little more comfortable. To cater for the expansion of stagecoach routes coaching inns were built or developed, often with the characteristic arched entrance to allow the coach and horses to enter the interior yard, where stabling was provided. To maintain good timing, horses had to be changed regularly, and grooms and ostlers were needed for their care.

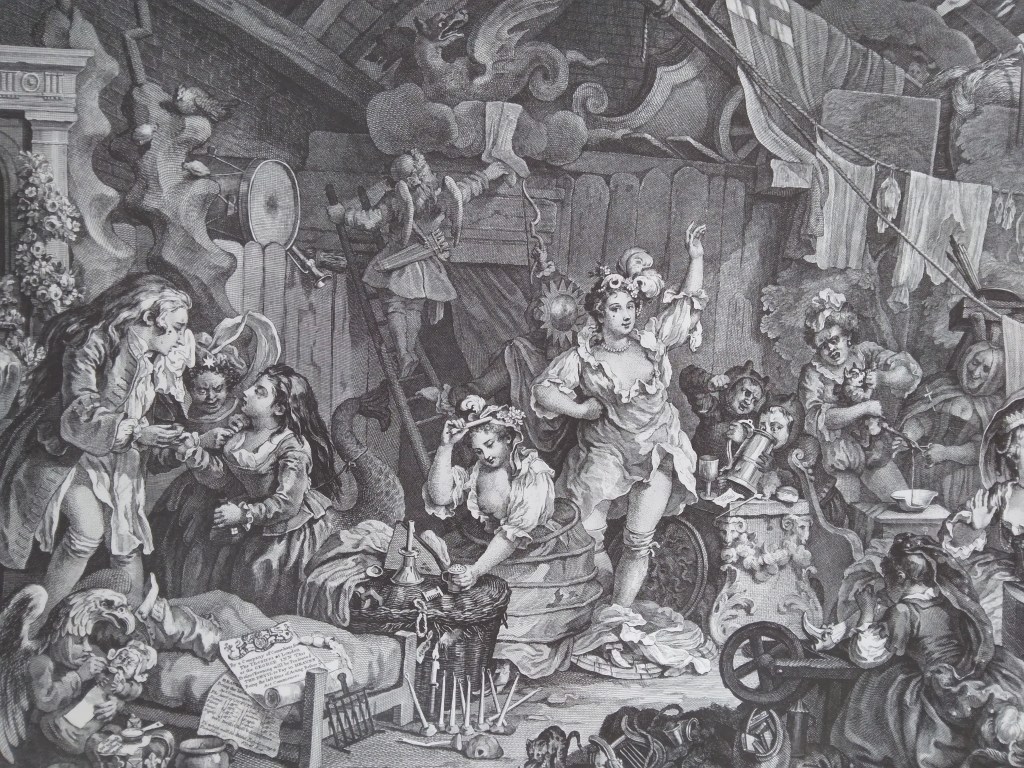

There was an important distinction between inns and ale houses. The former offered accommodation as well as food and drink, while the latter were more down market and, as the name suggests, dealt mainly in (possibly home-brewed) beer. But even in the inns there were class distinctions: gentry in their private carriages or on horseback were more welcome than the occupants of stage coaches, while those on foot were often turned away. The owners of inns were frequently caricatured as greedy and grasping, in particular landladies, while the chambermaids were often portrayed as warm-hearted and generous.

This is the situation shown in Fielding’s humorous novel ‘Joseph Andrews’ (1742), which vividly portrays life on the road. Joseph, the hero, is robbed at the roadside, but is rescued by a passing coach and taken to the nearest inn, the Dragon. The company are sitting in the kitchen by the fire:

The discourse ran altogether on the robbery, which was committed the night before, and on the poor wretch, who lay above, in the dreadful condition, in which we have already seen him. Mrs Tow-Wouse said, ‘she wondered what the devil Tom Whipwell meant by bringing such guests to her house, when there were so many ale-houses on the road proper for their reception? But she assured him, if he died, the parish should be at the expense of the funeral.’