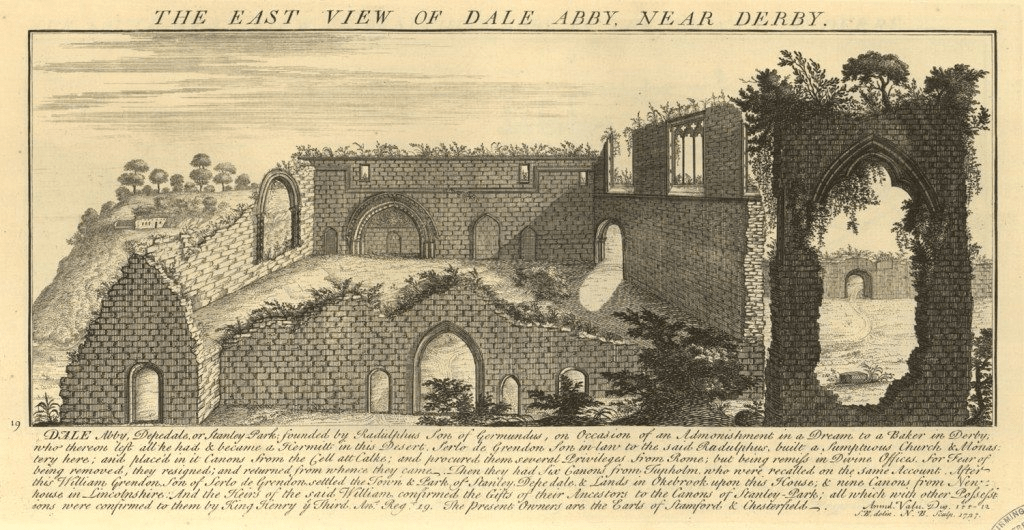

It’s difficult to get lost today. Google maps will display every street in the city, and spell out your quickest route, while in the country apps such as OS Maps will tell you exactly where on the path you are standing. The appeal of this technology is obvious – not just saving time, but also removing the fear that you’re heading the wrong way, into the unknown. In Derbyshire and the Peak District, with thousands of miles of footpaths, this reluctance to risk being lost results in crowds of visitors heading for the same honeypots such as Dovedale, Mam Tor, or the Cromford Canal, with predictable results.

It has been argued that the experience of getting lost can be valuable for our development, and we can cope better with that fear if we develop a strong sense of direction. Moreover, research has shown that the more children are allowed to roam freely, the better sense of direction they acquire. Although there must be marked individual variation, it seems that children today are restricted to a much small radius of ‘free movement’ – perhaps a few hundred yards – instead of the miles that children wandered away from home in previous generations. Of course, it can be argued that there is good reason for the restriction, but if children are barely allowed out of sight of their home they have little possibility of feeling lost – and then finding their way back.

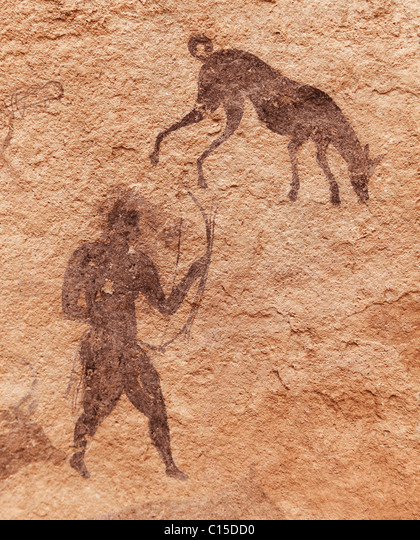

How do we get a sense of direction? Moving through a landscape we notice and memorise a series of landmarks, while the position of the sun should provide an additional bearing (provided it’s at least partly visible). To return, the landmarks are revisited. The second time you make the journey, the landmarks are stored in your memory, even after a gap of months or years, as most walkers have found. Our nomadic ancestors, travelling through an unmapped countryside thousands of years ago, must have achieved an advanced ability to find their way, using perceptions unknown to us.