Between Buxton and Youlgreave, high up above the Derbyshire dales, Arbor Low is the largest henge monument in the north of England. The November morning I visited was bleak and grey, with a keen wind from the west and a temperature barely above freezing. Unsurprisingly I was the only visitor when I arrived, although another car pulled up in the layby shortly after. I walked up the farm track for several hundred metres to where an English Heritage board gave some rudimentary information. There are two related sites here: the circular henge and Gib Hill, apparently a tumulus, a field away to the west. Then I walked up to the farmyard, where a small sign asked for a modest £1 for using ‘private land’.

Many farms in the Peak District are tatty; this one looked particularly run-down. A woman was pushing a wheelbarrow full of firewood through the yard – nobody else was around. The cattle were still in the fields, so the stall block was empty. There was a sign advertising‘B & B’ by the roadside, but I couldn’t imagine anyone choosing to stay in such a bleak location. Presumably they earn a few pounds a week from visitors’ contributions, but there was no attempt to offer tourist fare such as teas or postcards.

Beyond the farmyard Arbor Low is a circular bank containing a ditch and inside that over 40 stones, lying flat, with a few more stones at the centre. Impressive enough, especially given the situation, with a view of several miles in every direction. There are information boards at both the henge and the Gib Hill site, although these contain little actual information, beyond the standard visual recreations of scary looking people doing weird things. Apparently there has been no excavation here for a century, and so our knowledge of these places is even vaguer than usual with the prehistoric.

The contrast with the real Stonehenge is total. On Salisbury Plain coaches full of tourists, many from abroad, arrive every hour. There are lavish facilities for visitors, and a hefty £13.90 price tag to buy the timed tickets. Hundreds of visitors wander round the circle every hour. Scores of books and dozens of TV programmes have attempted to reveal the ‘secrets of the circle’. Yet, standing on the bank around the fallen stones, with an icy wind in my hair, I felt far closer to the past, whatever it contained, than I ever had in the south.

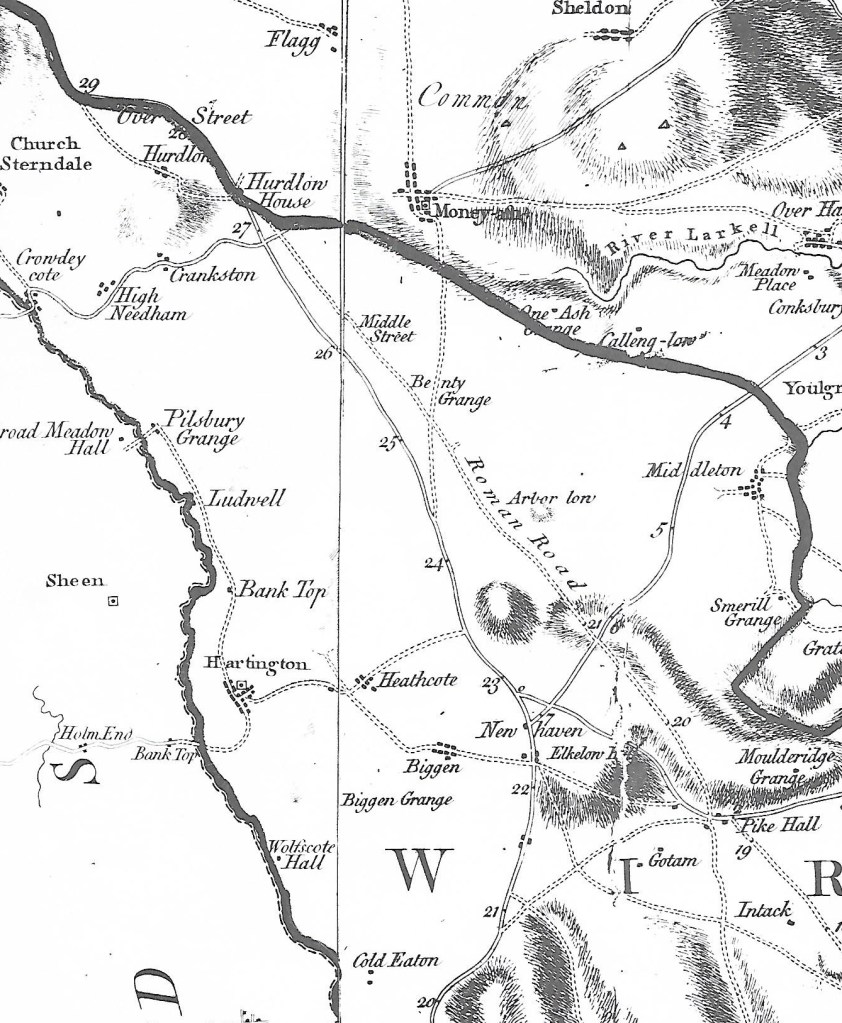

Burdett’s map of 1767 showing The Street north of Pikehall

Something not mentioned by English Heritage is that a Roman road ran through this area just 100 metres away, south east from Buxton, and that this probably followed the line of an older ridgeway. A henge monument on the scale of Arbor Low must have attracted visitors for (presumably) seasonal festivals from all over the district, and so the proximity of the henge to the road is not mere coincidence. It can be seen that the eighteenth-century turnpike did not follow the exact route of the older road, which remained in use until the time of Burdett’s map, but which has now disappeared except as a parish boundary. Overall the route presents a classic example of a road that may be at least four thousand years old, starting as a ridgeway serving the henge and other sites nearby, then being re-engineered by the Romans, and more recently re-routed as a turnpike road.