Doll Tor, near Birchover

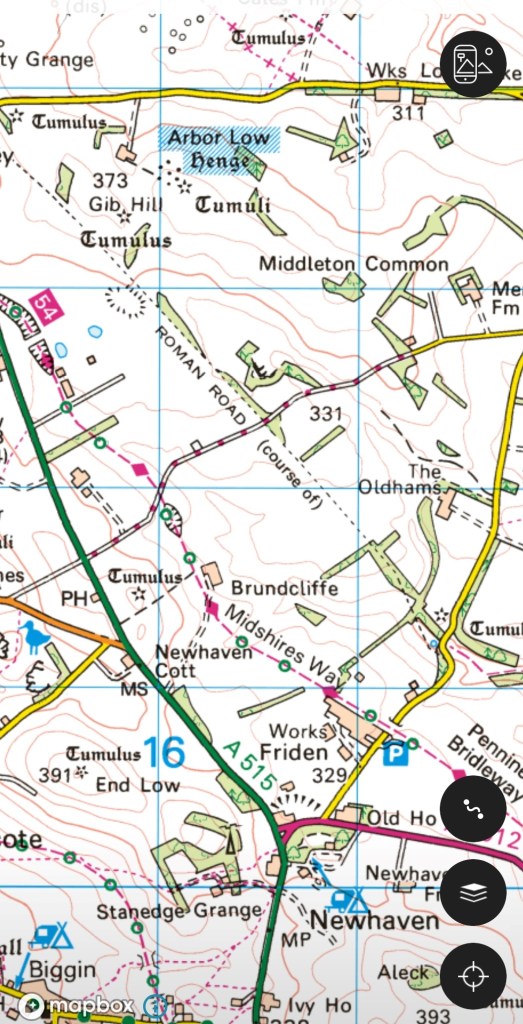

There are over a thousand stone circles in Britain and France, and Derbyshire has its share, ranging in size from Arbor Low (up to 50 metres in diameter) to much smaller versions, such as Doll Tor (above). This latter is part of a cluster of circles, with the Nine Ladies on Stanton Moor close by, and Nine Stones Close on Harthill Moor not far off. There may have been more circles in the past, since we have evidence that some have been pillaged for their stone (Nine Stones actually only has four stones), and others destroyed as pagan symbols by God-fearing landowners. Most of the surviving circles are on moorland or high pastures, which raises the question whether the reason for their survival was their location on land of little value. Others might argue that the circles were built on high places for astronomical purposes, to observe sunrises for instance. In fact, although the circles have been studied, measured, excavated and theorised about for over two hundred years, we still seem no closer to knowing their purpose

There does seem to be agreement that most circles belong to the Bronze Age, roughly 3,000 years ago, though obviously dating such basic structures is not easy. But over this time span many may have been altered, so there’s no guarantee we’re looking at the original layout. Some of the stones at Doll Tor, for example, have been re-set, and Bateman records seven stones on Harthill Moor in the nineteenth century (others claim that these stones have been raised to standing position, it being the only circle in the county with standing stones).

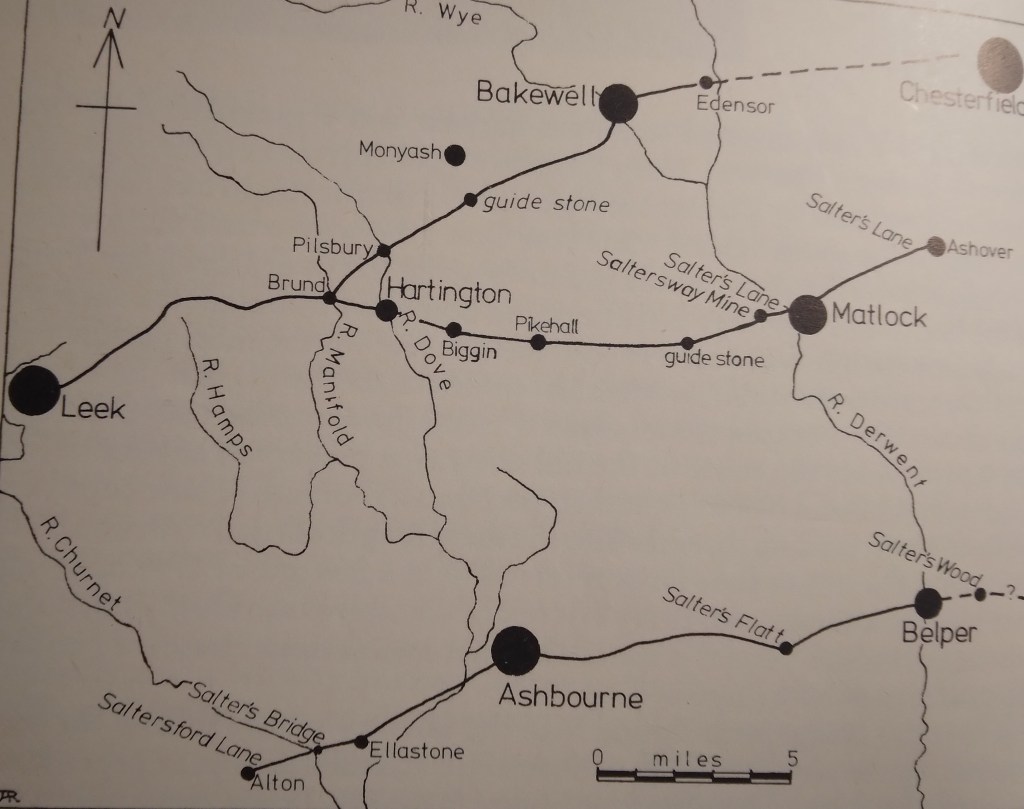

Some circles seem deeply unimpressive: The well-known Nine Ladies, for instance, hardly compares with the majesty of Stonehenge. Yet, large or small, there is still no clarity on why these monuments were built. Vague talk of ceremonial sites or astronomical observation is pure speculation and seems as dubious as Victorian ideas of ‘druidical temples’. Perhaps there is a simpler explanation. Before the Romans arrived the British lived in round, wooden houses – effectively the only shape of building they made. A stone circle can be seen as a symbol – a permanent representation – of their house, which proclaimed ownership of the land to all travellers and passers-by. The circle would be a permanent claim to their property, in days before the Land Registry. Both Arbor Low and Nine Stones are on prehistoric routes (the Street and the Portway), but other circles would have been visible from the tracks across the uplands.