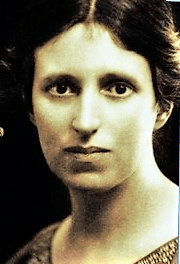

Jane Austen 1775-1817

A significant tourist industry has grown up around Jane Austen and Derbyshire. It is often claimed that she visited the county in 1811, stayed at the Rutland Arms in Bakewell, looked around Chatsworth and based Mr Darcy’s fictional house of Pemberley on this model. At least one film of Pride and Prejudice has used Chatsworth as a setting. However, there is no actual evidence that Jane ever visited the county, let alone wrote about it.

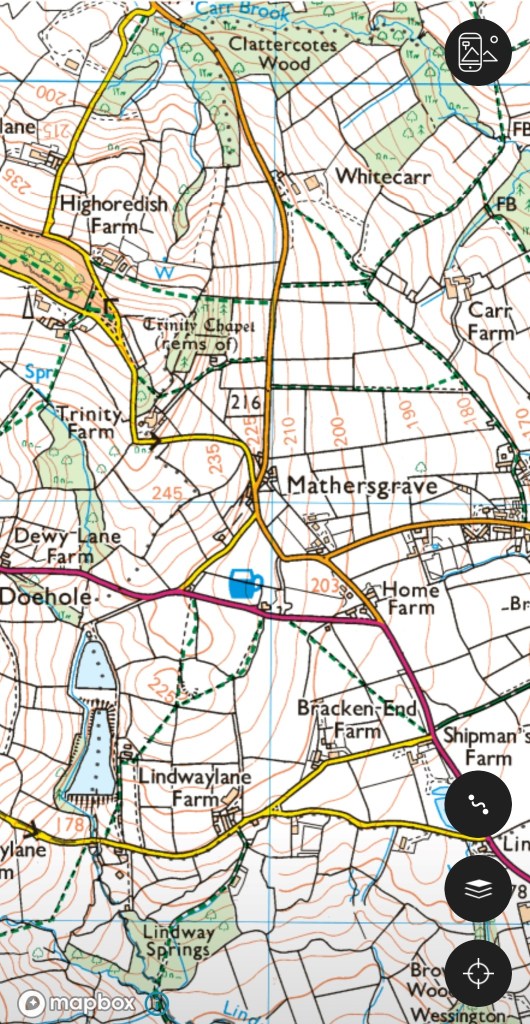

In Pride and Prejudice the heroine, Elizabeth Bennet, is taken on a tour of the Peak District by her aunt and uncle. There is mention of Matlock, Chatsworth, Dovedale and the Peak as being the main attractions. They base themselves in ‘Lambton’, often taken to be Bakewell, from where Pemberley is a three-mile drive. When they visit the house its setting makes a positive impression on Elizabeth: ‘…it was a large handsome stone building, standing well on rising ground, and backed by a ridge of high, woody hills – and in front a stream of some natural importance is swelled into greater …’ . This description has encouraged the identification with Chatsworth, but there are three objections to the theory. First, as mentioned above, there’s no record of her visiting the area, second the description of the house is generic, and could apply to many mansions from this period. Landscape fashion from the eighteenth century had created dozens of similar park-like vistas and Austen would have seen engravings such as the one above. Finally Pride and Prejudice, although only published in 1813, was largely written in 1797, 11 years before her supposed visit to the county.

The search for originals of fictional people and places is quite pointless, since it assumes that authors have no powers of invention. More interesting is the light that the story sheds on early tourists in the Peak. Even if she had never visited Derbyshire, Austen was well aware of the tourist sights, which wealthy travellers could best enjoy by hiring a chaise, a small light carriage for two or three people. Complete with driver, this would cost about a guinea a day, roughly £100 in modern money.