This figure from Youlgrave church is thought to represent a pilgrim, with his (or her) staff and waist-hung satchel. We often think of pilgrimage in terms of the great medieval shrines of Christianity such as Santiago or Canterbury, but during the high middle ages (about 1100 – 1300 CE) many pilgrimages must have been more local, perhaps within a day’s journey of the pilgrim’s home. In Derbyshire, abbeys such as Dale as well as churches like St Alkmund’s in Derby would have attracted pilgrims. The main draw was the burial place of a saint or the ownership of a holy relic, such as a flask of Mary’s milk.

Pilgrims hoped that being close to the remains of a holy person would benefit them in some way. Many were seeking a cure for an illness, often with the belief that a particular saint would help with certain conditions. Others might be making the journey as a penance, to compensate for some crime or misdemeanor. St Alkmund was a local saint who was murdered in Derby in the eighth century, and whose impressive stone sarcophagus can be seen in Derby Museum – the (rebuilt) church was demolished to make way for the city’s ring road.

Another local saint, although actually in Staffordshire, is St Bertram at Ilam near Ashbourne. He also lived in the Saxon period, becoming a hermit after his wife and child were eaten by wolves. One unusual feature of the church is that the shrine of the saint has survived, perhaps due to the remote location of the village. Most aspects of pilgrimage, such as shrines and relics, were removed during the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century. Yet although discouraged, pilgrimage was hard to suppress, and saw an effective revival in the growth of spa towns such as Buxton in the eighteenth century.

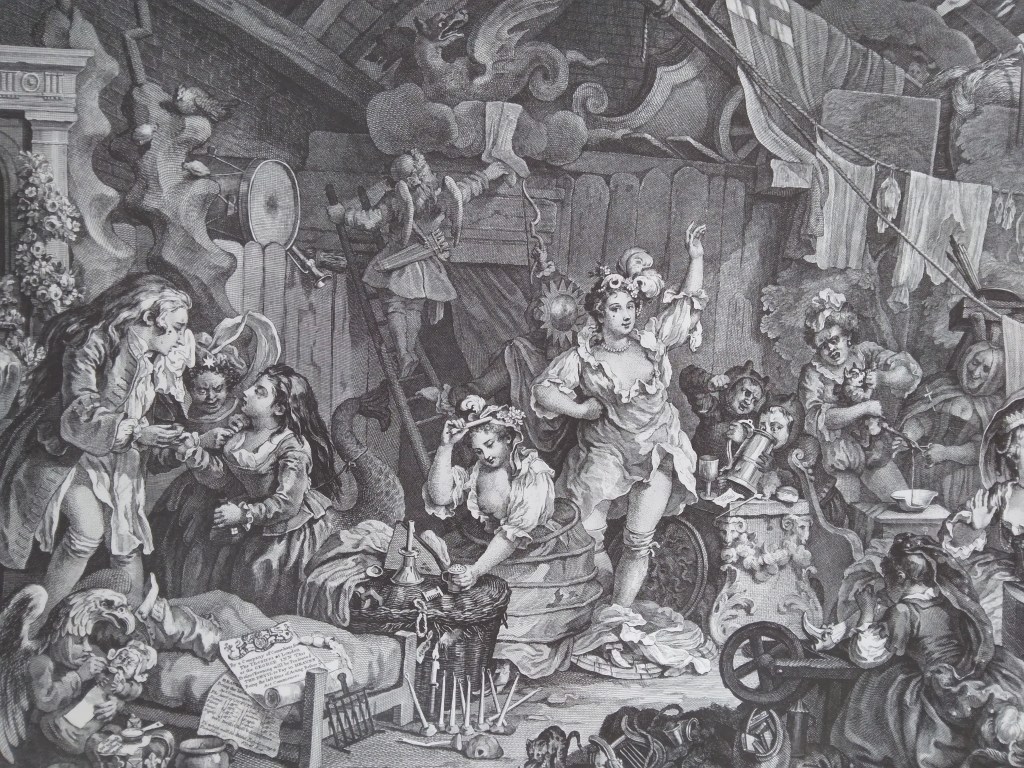

In Britain there are few relics of pilgrimage, but in Catholic areas of Europe such as Spain or Bavaria it is possible to find displays of ex-votos such as the example above. These are often small paintings of a miracle rescue or healing brought about by the local saint, and given to the church in thanksgiving. In other places models of the afflicted body part, such as arm, foot or head, are displayed. Clearly, in an age of very limited medical knowledge, making a pilgrimage was often seen as an effective remedy.