In the age of electronic messaging it is easy to forget the revolution in communication caused by the introduction of the penny post in 1840. This novel system of using stamps to pre-pay letters to anywhere in the country allowed working people, for the first time, to keep in touch with friends and relations, at a reasonable price. There was a huge increase in mail, and consequently post offices were opened in rural areas to organise the collection and delivery of letters. At this time country districts were more densely populated than today, and letters had to be delivered to widely scattered cottages and farms. Consequently, rural postmen (and women) were recruited, with routes of up to 15 miles, to be walked in all weathers for the delivery and collection of mail.

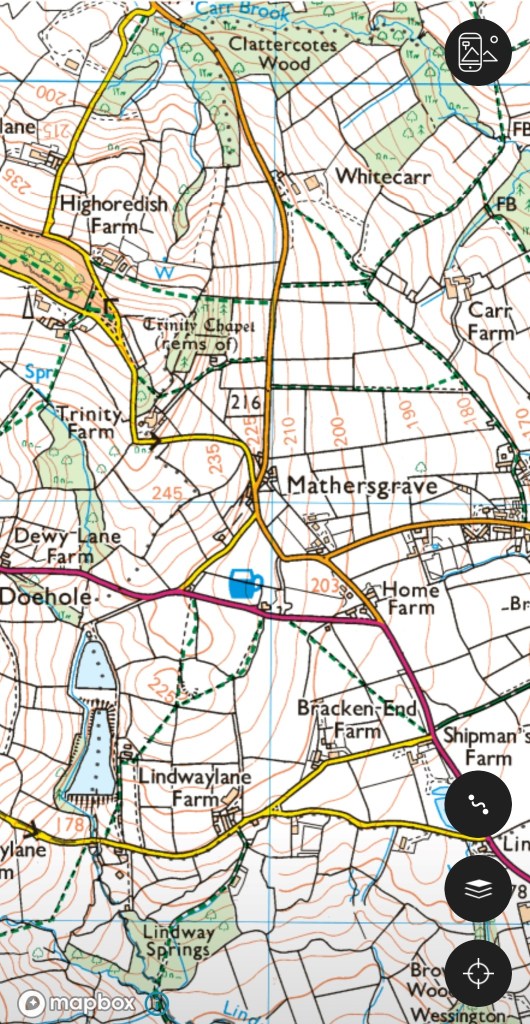

When the new system was introduced the postmen tried to reduce their ‘walks’ by finding short cuts between the scattered houses, thereby opening up new paths in places. However, today there is little record of their remarkable work, although some posties were still delivering mail on foot up to the 1970s, despite the general introduction of bikes and later, vans. Derbyshire must have had dozens of such forgotten postmen, while in Cumbria Alan Cleaver has been collecting memories of their lives, as recently featured on BBC Radio 4 in ‘Open Country’.

It’s hard to imagine anyone opting for a job today that involved a daily walk of 15 miles. Not only were letters delivered and collected daily, but the arrival of the post broke the intense isolation of much country life 150 years ago – there were cases of people sending letters to themselves, in order to have the postman call! Postmen were known to read letters out for folk who were illiterate, as well as bringing news from neighbours. Deliveries were even made on Christmas Day, as DH Lawrence recorded when living at Middleton by Wirksworth in 1918. Another notable change is the soaring cost of a stamp – compared with the Penny Black at one old penny, a modern second class stamp costs 85 new pence – 204 times more expensive!