Roman military dominance depended on its well-known road system, which not only allowed troops to move quickly, but also allowed messengers to ride rapidly with news or orders. To accommodate such travellers a kind of guest house, called ‘mansio’ in Latin, was built at regular intervals on the main roads, offering fresh horses as well as food and lodging.

Just over the Staffordshire boundary, south of Lichfield, are the extensive ruins of a Roman settlement built at the junction of Watling Street (near the line of the A5) and Ryknield Street, which continues to Little Chester and beyond. Both were important Roman roads, and this was first the site of a fort, then a mansio was built, and subsequently a small town grew up around it, known to the Romans as Letocetum.

The remains of the settlement can be visited in the village of Wall, on a gently sloping site only a few hundred metres from the noisy M6 toll road. In the foreground of the picture above are the ruins of a bath house, so that tired wayfarers could have a warm soak after a day in the saddle. It seems strange to imagine public baths in such a remote spot, and it would be interesting to know who was allowed to use them.

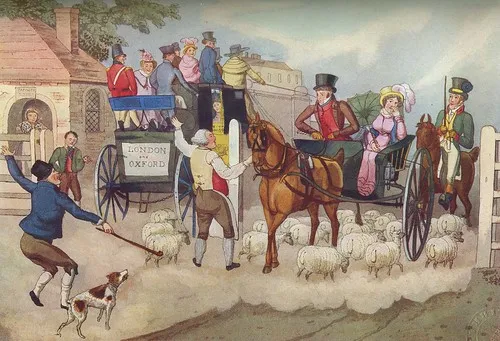

Despite the care with which this site is preserved by English Heritage it is hard to imagine it in its heyday. But an inscription from Aesernia in Italy of the dialogue between an innkeeper and a departing guest gives more flavour, and can be translated as: ‘Innkeeper, let’s settle our account. One measure of wine and bread, one coin; some stew, two coins. Agreed. The girl, eight coins. That, too, is agreed. Fodder for the mule, two coins. That animal can take me to my destination…’.