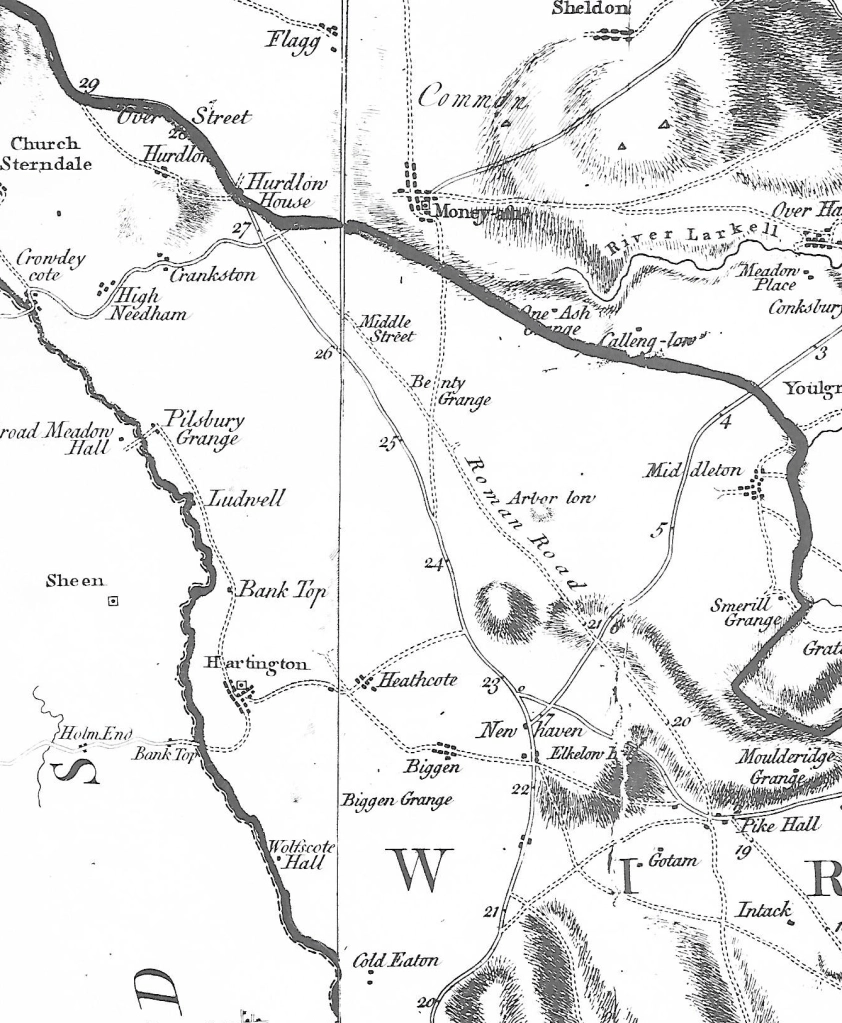

Derbyshire has plenty of stone, as shown by its characteristic dry-stone walls, and walkers may find pillars of stone, like the example above, set in the landscape for no apparent reason. Impossible to date, and clearly not redundant gateposts, they can only be assumed to mark some long-lost route. In other places there does seem to be a link to an old track, as with the large stone below, less than a mile above Wirksworth on the Brassington road, on the line of the Portway.

Again, it’s impossible to date a megalith like this, but clearly a lot of trouble was taken to erect what must have been a route marker. Given that many stones like these have been re-used for building, and others deliberately destroyed as symbols of paganism, we can imagine a prehistoric landscape well populated with such pillars. Surviving stone circles reinforce the idea of stones having power and importance, and this may have continued into the early Christian period, from about 600 CE.

Presumably the first Christian missionaries set up ‘crosses’ like this example in Bradbourne as symbols of the new beliefs; although badly worn a crucifixion scene can be found near the base. Similar crosses can be seen at Bakewell church (found on Beeley Moor) and Stapleford, on the Portway in Nottinghamshire. Although referred to as crosses they are actually simple carved pillars, which suggests an attempt to Christianize a pagan symbol.

Both of these monuments are thought to date from the ninth century, far older than the church they adjoin. The cross was only adopted as a Christian symbol in 692 CE, and one of the earliest examples of the ‘new’ pattern can be seen at Eyam churchyard (part of the shaft appears to be missing). It is always possible that these crosses were moved into the churchyards at some point, and they may originally have been route markers.

In Medieval Britain crosses became more common and varied: wayside crosses, boundary crosses, market crosses and later, memorial crosses. In some cases they may have had the dual role of showing the way and indicating the next pilgrim shrine; this cross base at Cross Lane near Dethick seems to mark a route that extended south to Shuckstone Cross, only a mile away, and beyond. These (now lost) crosses would have protected travellers as well as guiding them to the holy places.

See: Sharpe, N. ( 2002) Crosses of the Peak District, Landmark