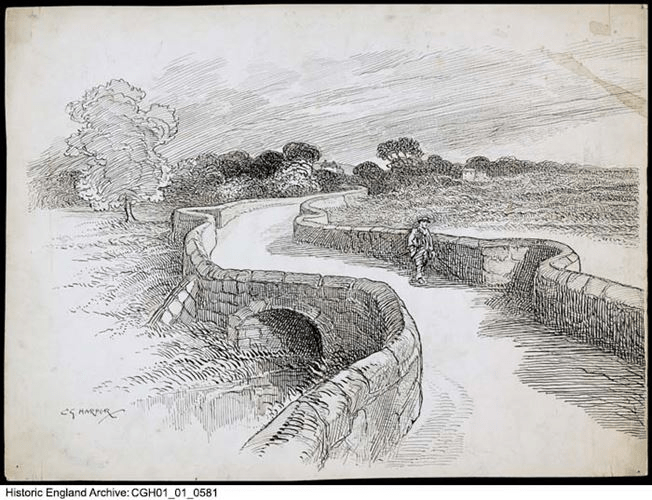

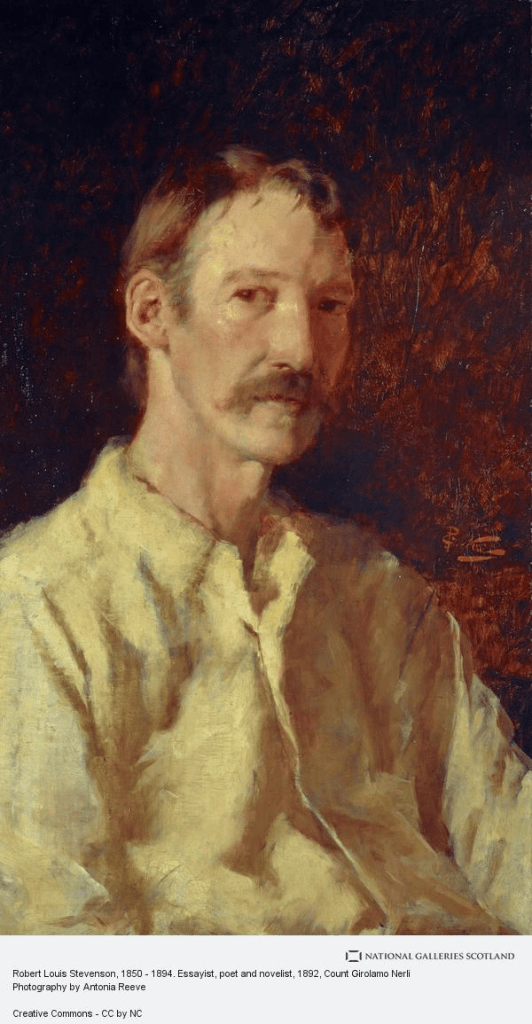

Give to me the life I love, Let the lave go by me, Give the jolly heaven above And the byway nigh me. Bed in the bush with stars to see, Bread I dip in the river, That's the life for a man like me, That's the life for ever. Robert Louis Stevenson wrote his poem The Vagabond in the 1870s, influenced by a mid-nineteenth century enthusiasm among some intellectuals for the open road and the free life. Before this only the poorest travelled on foot, but now writers began singing the praises of walking, and even mixing with nomadic outcasts such as gypsies. Stevenson reinforced his poetry with experience, his pioneering Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes (1879) is his account of a 12-day hike through the hills of this French region, sleeping rough and struggling to control his animal.

George Borrow

Twenty years earlier, the less well-known but probably more remarkable George Borrow had published his autobiographical novel Lavengro (1851), based on his wanderings in England and Wales and his meetings with gypsies, whose language (among many others) he claimed to have learned. Borrow was certainly physically remarkable, a tireless walker who went on to work for the British and Foreign Bible Society in their quixotic attempt to bring the Word to Spain. His account of his travels, published as The Bible in Spain, reveals a man of considerable stamina, riding around (Carlist) war-torn Spain with a donkey-load of Bibles while maintaining his flirtation with the world of Romany.

Mathew Arnold, swinging between poetry and philosophy

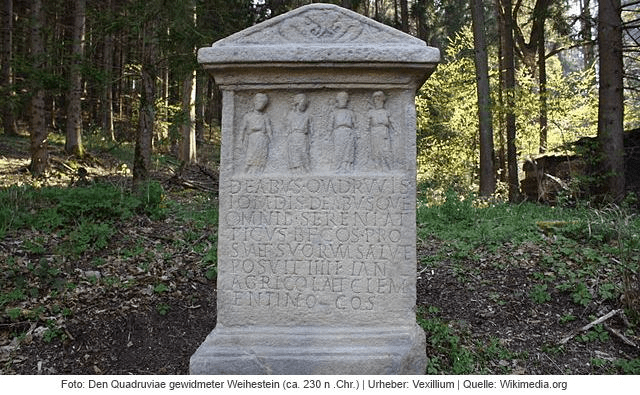

Another key work on this theme is Mathew Arnold’s The Scholar Gypsy of 1853. The longish poem tells the story of an Oxford student who becomes disillusioned with academia and joins a band of local gypsies, hoping to learn their secret lore:

The story of the Oxford scholar poor, Of pregnant parts and quick inventive brain, Who, tired of knocking at preferment's door, One summer-morn forsook His friends, and went to learn the gypsy-lore, And roam'd the world with that wild brotherhood, And came, as most men deem'd, to little good, But came to Oxford and his friends no more. Although it seems unlikely that Arnold took to the road himself, the poem expresses the doubts that were beginning to emerge about the destination of Victorian society, and the fascination with apparently more primitive or ancient cultures. In this sense Arnold was well ahead of his time, with these concerns becoming more prominent in the twentieth century. Writers such as Walter Starkie, an Anglo-Irish academic, who reprised Borrow with his wanderings in Hungary with the gypsies in the 1930s, as described in Raggle-Taggle (1933), continued this theme, while more recently there has been a positive flood of writers taking to the hills, tracks, lanes and even rivers in their eagerness to escape from the contemporary world.

Starkie in full flow