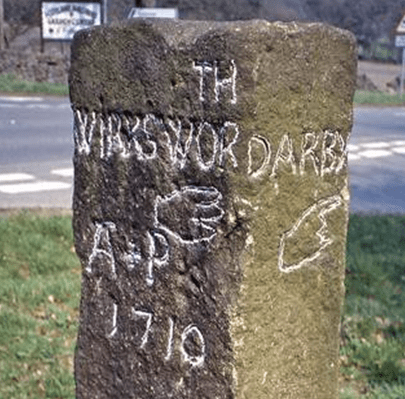

There are several ‘portways’ in England, such as the route over the Long Mynd in Shropshire, but the Derbyshire Portway seems to be the longest and the best-researched. The route in Derbyshire was first suggested by Cockerton, an historian from Bakewell in the 1930s, who based his idea of a long-distance route on a string of ‘port’ place names such as Alport and Alport Height, which can be linked together in a roughly north-south alignment by existing tracks and paths. These place names are reinforced by references to a ‘Portwaye’ in some medieval documents and two Portway lead mines. Cockerton discussed the origin of the name ‘Portway’ at length, without coming to a definite conclusion. But it seems clear that the word is Anglo-Saxon, and was applied by them to pre-existing, non-Roman routes. Some have suggested an origin linked to ‘porter’, that is someone who carries, but then all roads are for carrying goods. The common Anglo-Saxon word for road was ‘way’, except for the old Roman roads which were ‘streets’. So a ‘portway’ was something special.

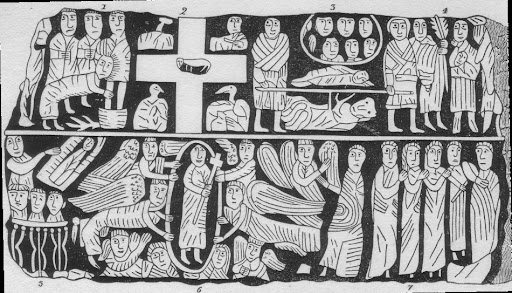

A ‘port’ suggests a place of safety and shelter, so I think a portway was a a long-distance route which had ‘ports’ for travellers at intervals of roughly ten miles. These might have been similar to the caravanserai found in the Middle East – defensive sites where wayfarers could sleep, cook and graze their animals overnight. In Derbyshire these are likely to have been on high ground for defence, and a string of probable sites can be identified, from north to south: Mam Tor, Fin Cop, Cratcliff Rocks, Harborough Rocks, Alport Height, Arbour Hill at Dale and Arbour Hill in Wollaton Park. It is noteworthy that three of these have a similar ‘arbour’ component, and a harbour of course is similar to a port.

Several of these sites, including Mam Tor, Fin Cop and Harborough, have been excavated and evidence of occupation, such as pottery, has been found. But permanent settlement in such high and waterless places seems unlikely, while the designation ‘hill fort’ is too vague. Far more likely that they served to protect tired travellers, and thus answered a question too rarely asked by pre-historians – how did merchants, drovers, priests, soldiers and pilgrims make lengthy journeys before the arrival of inns?