When I was a child we were occasionally driven into Derbyshire as a holiday treat, and coming down the Via Gellia was one highlight of such trips. It seemed a very romantic route, winding and well-wooded within the steep-sided valley, with mysterious caves inviting exploration. Today the road seems a little less fascinating, more overgrown with trees, and with massive quarry trucks weaving round every bend, yet it is of historical interest in that we know (unusually) when and why it was built, and by whom.

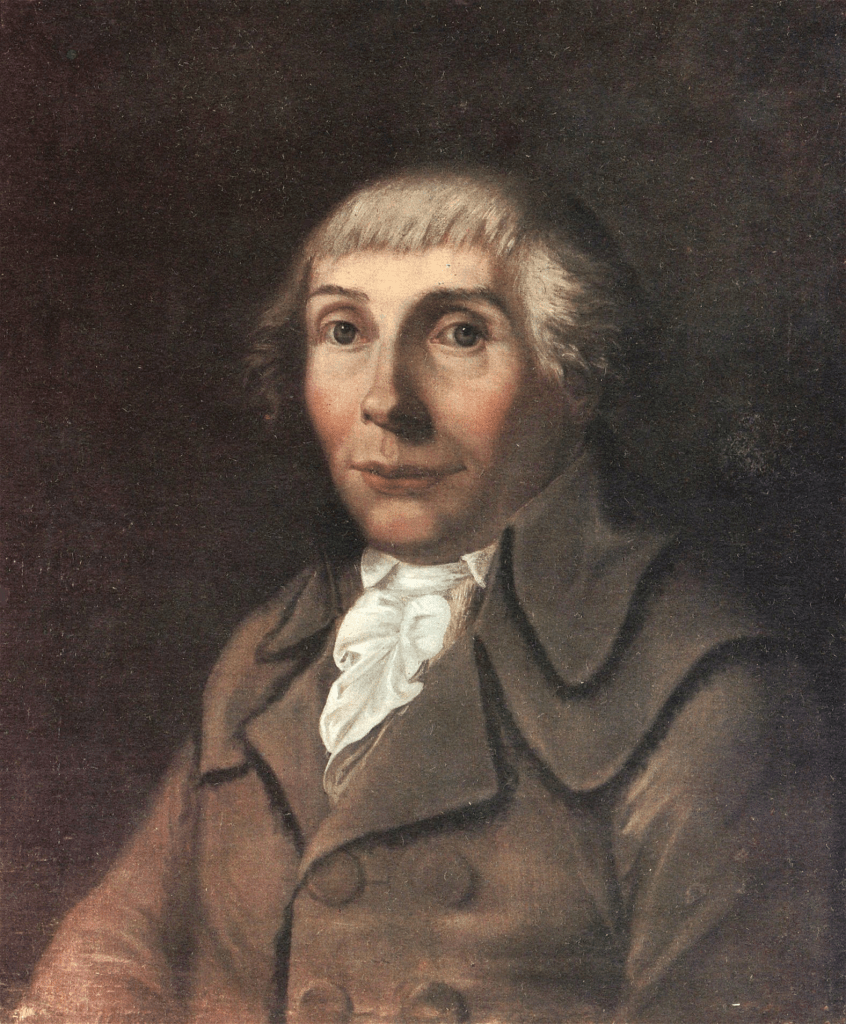

The Via Gellia is not the only road in Derbyshire to be named after a person; for instance there is the Sir William Hill near Eyam, but it must be a unique case of a Latinized family name! The Gell family had lived at Hopton Hall for generations, near where they had profitable quarries and lead mines. Philip Eyre Gell (1723-95) inherited the estate at the age of 16, but postponed marriage till he was 50, in 1773, when he married the 16-year-old Dorothy Milnes. Their first son, another Philip, was born in 1775.

Burdett’s map of 1791 shows a track from Cromford to the mill where the Bonsall Brook drops down the Clatterway, but nothing beyond that point. The building of the Via Gellia is generally dated to 1791/2, and was designed to allow carts of lead ore or stone to travel down from the Hopton area to the canal and lead smelters at Cromford. Nobody knows who gave it its name, but one possibility is Philip Gell’s second son Wiliam, an archaeologist who had visited the ruins of Pompeii. Perhaps his interest in Roman civilization and knowledge of Roman road names such as the Via Appia led him to christen his father’s road in Roman style, hinting at an improbable family history dating back over a thousand years?

Tufa Cottage, situated about half-way down the route, must have been built by the mid-nineteenth century, originally for a gamekeeper on the Gell estate. Tufa is a kind of porous limestone found locally, with a distinctive coarse texture. Today it is notable for the cable car in the front garden!