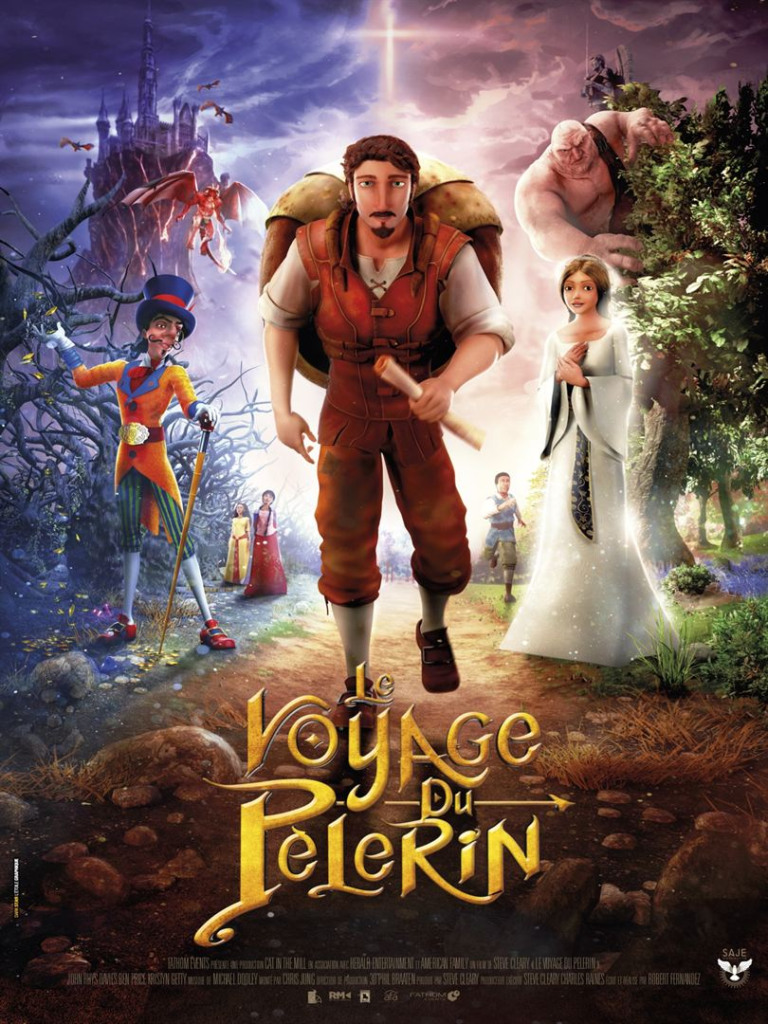

The Pilgrim’s Progress, from this World to that Which is to Come must be one of the most influential books ever published in English. Today it has become common to speak of ‘my cancer journey’ or ‘our journey through bankruptcy’, using the metaphor of life, or part of life, as a journey. It is also normal to talk about making a ‘pilgrimage’: to Lennon’s birthplace, for instance. But this is not a new concept, as shown by the extraordinary popularity of John Bunyan’s work from the late seventeenth century into modern times – the concept of life as a spiritual journey or pilgrimage has not gone away. First published in 1678, Pilgrim’s Progress has been translated into 200 languages, and never been out of print. An allegorical story of a man’s (Pilgrim’s) search for spiritual salvation, a quest which takes the form of a journey through a series of dramatic dangers, the work was in many ways a proto-novel, presenting an exciting story in vivid language.

John Bunyan was born in 1628, in Bedfordshire, and enlisted in the Parliamentary army aged 16, during the English Civil War. It was a time of fervent religious and political debate, and Bunyan was probably influenced by the more radical, puritan elements in the army. He left the army after three years and became a tinker, a trade he had learned from his father. This peripatetic occupation must have made him more conscious of the dangers of travel. He also began preaching for a nonconformist group in Bedford. But the return of the monarchy in 1660 made it an offence to preach outside the Anglican church, and Bunyan was arrested, tried and imprisoned. As he refused to obey the law he went on to spend 12 years in Bedford Gaol, during which time he wrote the first part of Pilgrim’s Progress. The book was an immediate success, so that on his release he was able to devote his time to further religious writings. This meant that until his death in 1688 he, his wife and children had some financial security, after the sufferings of the years in prison.

Perhaps the secret of the book’s enduring appeal is its simplicity. Who could forget characters such as Mr Worldly Wiseman or Lord Hate-good, or places like the Slough of Despond, The Valley of the Shadow of Death or Vanity Fair (a name invented by Bunyan but borrowed by Thackeray)? Pilgrim’s Progress was repeatedly cited by radicals in the nineteenth century as a major influence on their political development. For instance:

‘For the founding fathers of the Labour Party, it was a revolutionary manifesto to “‘create a new heaven and a new earth” … Robert Blatchford, who had practically memorized Pilgrim’s Progress by age ten, always found its political message supremely relevant: Mr Pliable we all know, he still votes for the old Parties. Mr Worldly Wiseman writes books and articles against Socialism …’.

(Source: The Intellectual life of the British Working Classes, Jonathan Rose)