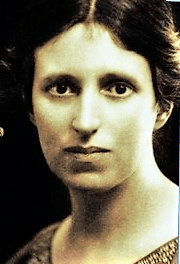

Today few young children walk to primary school alone, for a variety of reasons including parental perceptions of danger. In fact, the image of mum in a large Range Rover driving her offspring to the school gates has become a cliche. Yet 150 years ago children who were lucky enough to go to school often had to walk for miles, especially in rural areas. To some extent this walking may have formed part of their education, as was the case with Alison Uttley, who later became famous for her Little Grey Rabbit books. Alison grew up in a struggling farming family at Castletop Farm between Cromford and Lea Bridge. She didn’t go to school until she was seven, due to the remoteness of their farm on Hearthstone Lane.

Lea Primary School on Church Street, Holloway was chosen by her parents due to its good reputation. But the journey home, although only a mile and a half long, meant walking from school down to Lea Road, past John Smedley’s mill at Lea Bridge and then climbing up through Bow Wood on what is now a rough track (but which was the old road before the turnpike was built by the Derwent), and emerging from the wood just below the farm. Alison had to do this walk twice a day, in all weathers, and in winter the homeward stretch would be in the dark, for which she was given a lantern.

The path through Bow Wood

Clearly the fears she felt on her walk had a major impact, for she describes the journey in several books:

“I set off home, running for the first mile, for it was downhill and easy. Then I passed a mill and walked up a steep field where cows grazed. I came to the wood, and stopped at the big gate to light the candle in my lantern. I shut the gate softly so that ‘they’ would not hear. The treees were alive and awake, they were waiting for me…”

She obviously had a powerful imagination, and perhaps this walk could be credited with launching her career as a storyteller, since she sometimes persuaded a school friend to walk with her, with the incentive of listening to the stories that Alison made up as they walked.

Alison’s walk to school can easily be followed today, either starting from Cromford Station and walking uphill to Castletop, and then through Bow Wood to Holloway, or the reverse route starting from Lea Primary School.

Sources

Judd, D (2010) Alison Uttley, Spinner of Tales, Manchester University Press

Uttley, A (1951) Ambush of Young Days, Faber & Faber