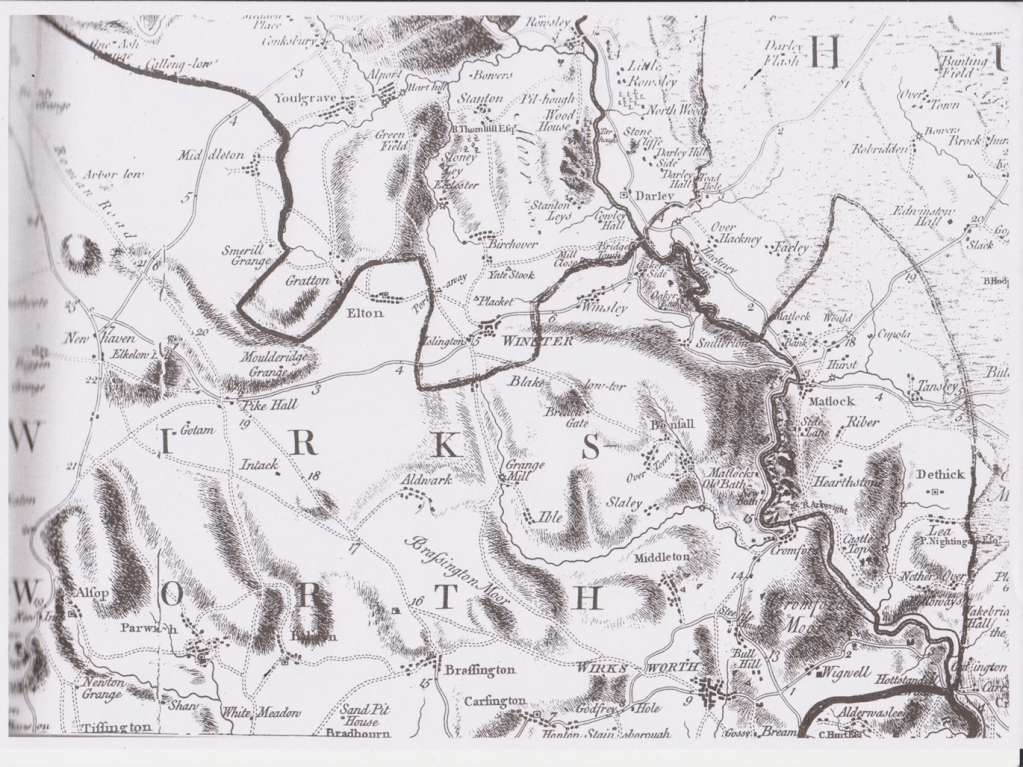

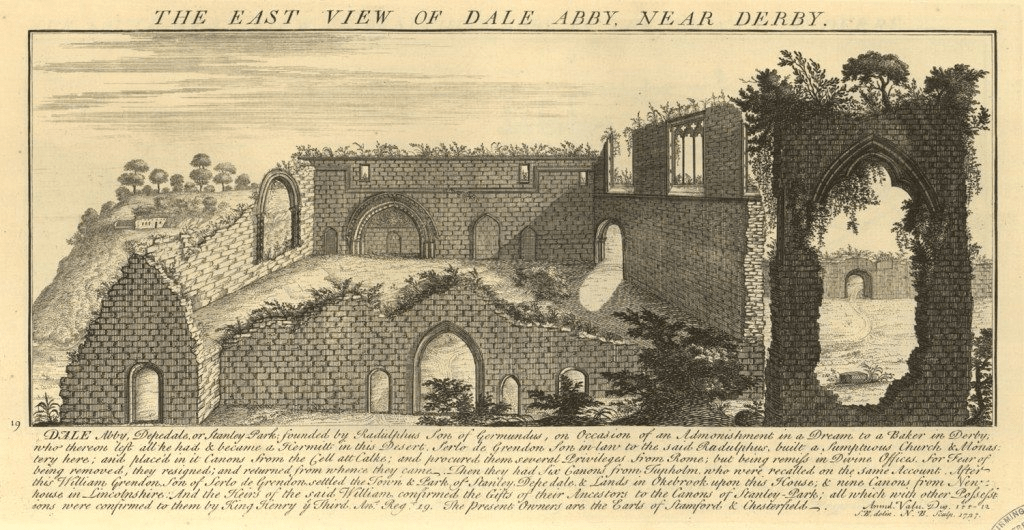

Compared with neighbouring Yorkshire, Derbyshire has hardly any visible remains of its abbeys. Even the location of Darley Abbey in Derby is uncertain, while Dale Abbey, between Ilkeston and Ockbrook, has just one solitary surviving arch (see below). The engraving above shows the state of the ruins in the eighteenth century, before the robbing of dressed stone had been completed. Yet at its height in the fifteenth century this abbey owned about 24,000 acres of land, throughout the county and beyond; endowments it had accumulated over the years. With only about 15 canons in residence, the job of administering these estates may have been given to lay people, but this task must have involved constant travelling. In addition, abbeys like Dale attracted pilgrims who came to pray before relics, in this case a phial of St Mary’s milk. For both reasons, Dale Abbey must have been sited on a good long-distance route.

The remains of the east window, Dale Abbey

The conventional view is that monasteries and abbeys were sited in remote, inaccessible places where the inmates could spiritually benefit from the tranquility of isolation. That may have been true at one time, but the running costs of both the abbey and its agricultural lands meant that two-way traffic steadily developed. In fact Dale was on the route of the Derbyshire Portway, linking it directly with Nottingham to the east, and to the northwest with Wirksworth and its estates at Griff Grange just beyond that town (‘grange’ suggests a monastic farm).

Dale Abbey was closed in 1538 (by William Cavendish) and its huge estates, consisting of churches and mills in addition to moors, woods and fields were sold off. By this time the influence of Protestantism was undermining the twin ideals of the monastic life and pilgrimage. The buildings were soon pillaged: some stained glass, for example, being taken to nearby Morley church. Today the village of Dale provides good walking, one of England’s few semi-detached churches (another survival from the Abbey) and a remarkable hermitage above in the woods, supposed to have been created by a Derby baker who sought a religious life there in the twelfth century.