The wheel is often cited as a critical invention in the development of our civilisation, and today wheels are so abundant it is difficult to imagine life without them. Yet they arrived in Britain relatively late – Stonehenge was built by a wheel-less society. The earliest wheel found so far, in Flagg Fen in Cambridgeshire, dates from about 1,600 BCE and is a solid wooden disc. The wheel above, from a museum in Avila, Spain, is over 3,000 years newer, and illustrates the complexity of making wheels almost without metal. It consists of five curved wooden sections, reinforced by a rim of five narrower pieces, all held together by ten spokes radiating out from a wooden hub strengthened by iron bands. Clearly the use of spokes makes for a much lighter wheel, reducing the effort for the carthorse.

These iron wheel rims were found in a chariot burial in northern Greece. They are thought to be Thracian, dating from the Roman period, and, remarkably, the skeletons of two horses were found in the tomb, buried in a standing position. The wooden part of the wheel has disappeared, but traces left in the soil show that it had spokes. Similar chariot burials have been found in Britain, notably in East Yorkshire, where a site at Pocklington in 2018 yielded the remains of a high-status burial of a chariot, thought to belong to the Iron Age (roughly contemporary with the Greek tomb), containing a man’s skeleton, along with the bones of two horses.

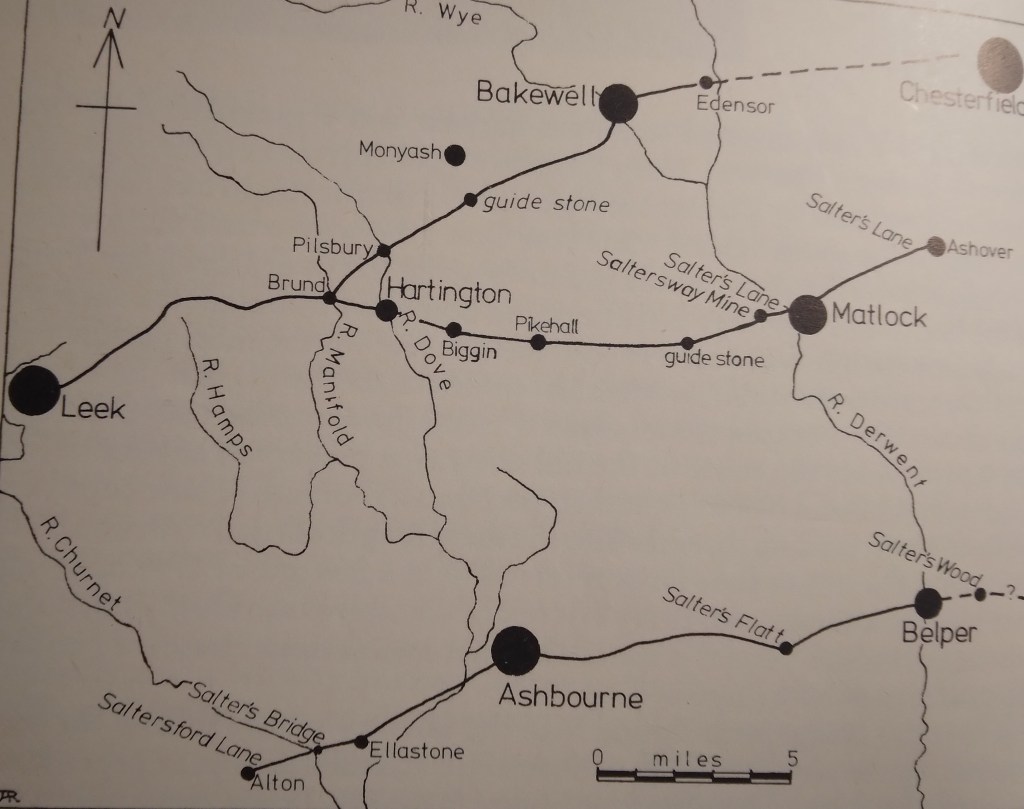

Wheeled vehicles such as carts, waggons and coaches were historically less common in north Derbyshire, due to the steep, poor roads and use of packhorses. However, for working lowland farms and for market journeys carts were more efficient than packhorses, needing only one horse to carry a ton of goods. With the improvements in road surfacing brought about by turnpike roads in the second half of the eighteenth century, all major Derbyshire towns were connected by regular coach services by the early nineteenth century. The picture above shows a passenger-carrying brake or charabanc outside the Sun Inn at Buxton, perhaps waiting for a tourist party to finish their lunch?