Many of the earliest novels were effectively ‘stories of the road’, their plots centred on the journeys their heroes were making – books such as Don Quixote and The Pilgrim’s Progress – while the form is still popular today e.g. The Lord of the Rings. This format provided the possibility of introducing a rich cast of characters and a variety of adventures, but also gives the modern reader an insight into travel at that period: naturally a dramatized picture but one that had some basis in reality. One of the best early ‘road novels’ is Joseph Andrews by Henry Fielding, published in 1742. Joseph, the hero, is a poor unworldly servant who flees the unwanted advances of his aristocratic mistress, Lady Booby, in London and sets off to visit his sweetheart, Fanny, in rural parts. He has only walked a few miles before he is robbed and stripped naked by a couple of heartless footpads, who throw his apparent corpse into a ditch.

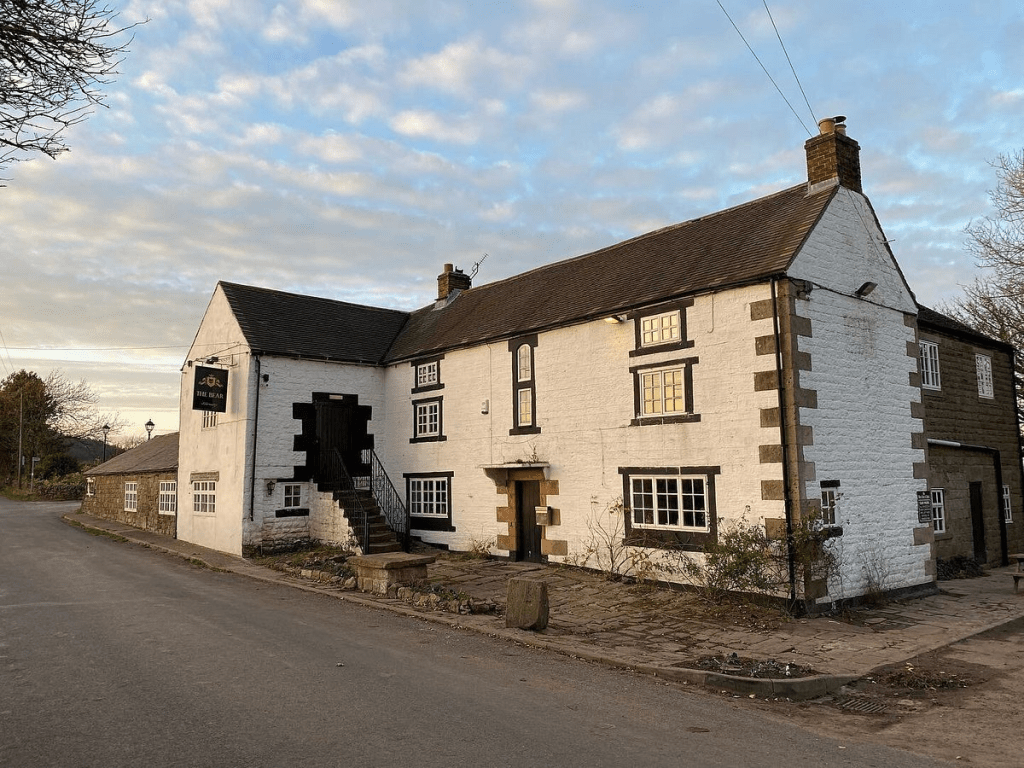

Luckily for Joseph a stagecoach pulls up, but every single passenger rejects the idea of rescuing the injured man – the ladies on account of his nakedness – until a lawyer points out that if they don’t take him to an inn they are possible accomplices to his murder. Only the postillion is prepared to lend Joseph his greatcoat, which allows him to board the coach. The coachman takes the injured man to the nearest inn, the Dragon, where he gets a sympathetic welcome from Betty, the chambermaid, who prepares a bed, and Mr Tow-Wouse, the landlord. However, neither Mrs Tow-Wouse, nor the local surgeon, nor the parson are prepared to help Joseph; the landlady complaining bitterly of her husband’s kindness and moaning that Joseph should have gone to an ale-house (inns, of course, preferred customers from the gentry).

All this in the first few chapters, and there follow enjoyable satires on inn-keepers, surgeons and vicars, culminating in Mrs Tow-Wouse discovering her husband taking advantage of Betty’s good nature, and Betty’s rapid departure. Happily, Joseph meets an old friend and together they set off for more adventures en route to Fanny. None of this needs be taken to be a realistic portrayal of eighteenth-century travel, yet it does reflect popular fears and concerns about the perils of wayfaring.