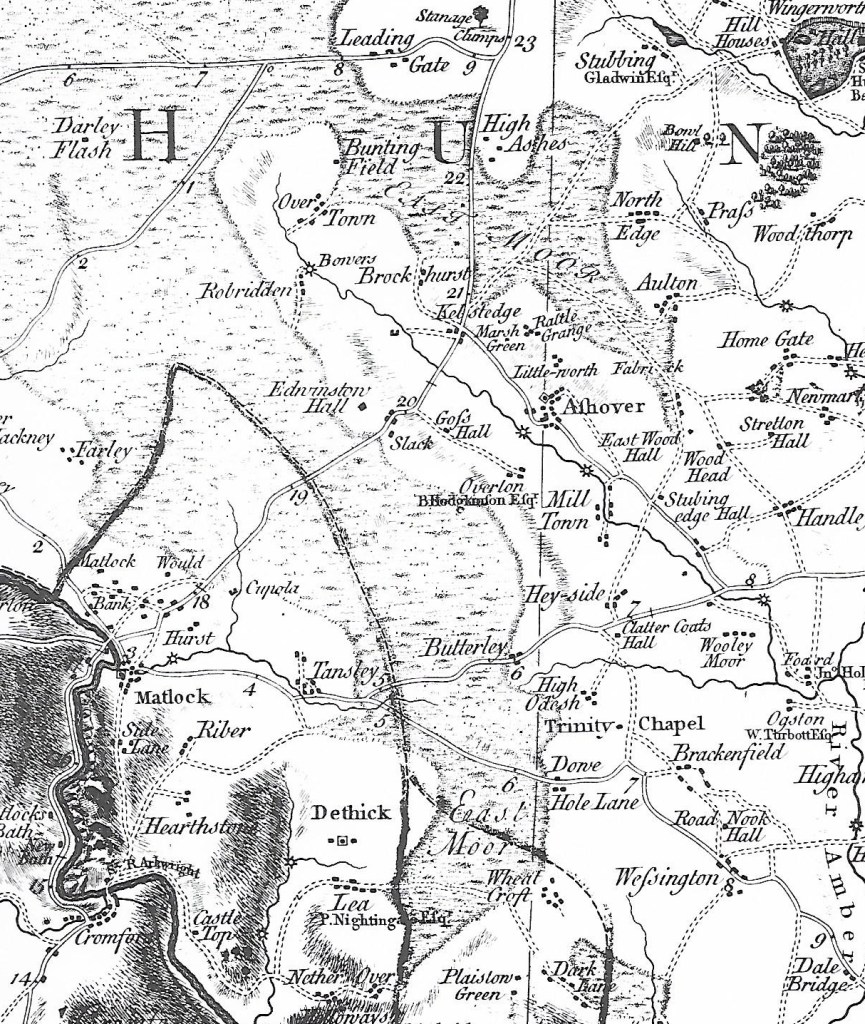

How many ‘Dark Lanes’ can you find on the Ordnance Survey maps of Derbyshire? I know several, for example the one running from Wheatcroft towards Plaistow Green, but there are probably more. In practice these lanes are usually shady holloways, so that the meaning of the name is obvious. But what is the origin of holloways, which are found all over the county, though more commonly on sloping ground?

Over hundreds of years’ use, these tracks, which were most likely no more than packhorse routes, became eroded by the constant wear and tears of hooves and boots. Rain would erode the surface soil until bare rock was reached, as can be seen on Longwalls Lane above. There may well be a relation between the depth of the holloway and the age of the route, though that would be difficult to calculate. But what is clear is that a deep cut lane, lying a yard or more below the surrounding fields, must be several hundred years old.

Holloway near Lea

The picture above shows a good example of an ancient holloway, running between Lea and Upper Holloway. Unusually it can be partly dated from an adjacent stile stone (below) of 1780, meaning that the holloway was in use 240 years ago (and probably many more). A steep road in Holloway, leading up to the moor, is called The Hollow, and must have linked to the Lea route as well as giving the village its name.

Over time, some holloways became waterlogged, especially in winter, forcing road users to travel alongside. The old path bottom gradually became overgrown and clogged with saplings and brambles, so that the right of way moved parallel but above. Today it seems reasonable to estimate that any holloway is earlier than an enclosure road (most of which date to the early nineteenth century), and may well indicate the local medieval road network.