This extract is taken from Chapter 1, Prehistoric Routes, pages 1-2

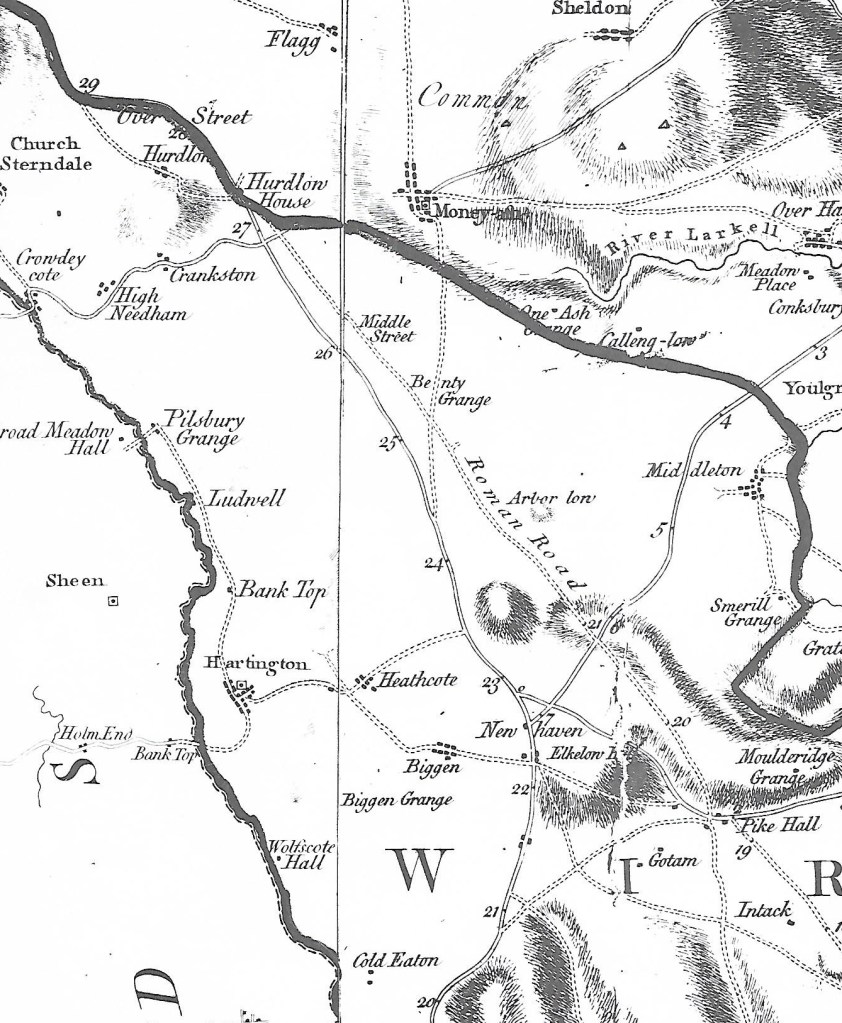

The northern part of Derbyshire has never been easy country to travel through. Even today, steep-sided valleys and winding roads can make for slow driving. The main national north-south highways find better routes, on either side of the Peak District. Inevitably, this topography has not produced rich farming country; in fact, historically Derbyshire was one of the poorest English counties. Much of the land is permanent pasture or moorland for grazing, and in the absence of intensive agriculture this has meant that there has been relatively little disturbance of ancient features such as burial sites or standing stones. Some, of course, have been lost, and there is documentary evidence of the deliberate destruction of prehistoric monuments by landowners, for religious or economic reasons. However, in comparison with lowland counties Derbyshire preserves quite a rich heritage of pre-Roman monuments such as stone circles and tumuli.

THE EARLY LANDSCAPE

It is difficult to know how different the Derbyshire landscape would have been in Neolithic (New Stone Age) times, about six thousand years ago. This was the period when people first began farming, probably by herding sheep and cows, and perhaps later growing some cereal crops. This was the beginning of settled habitation, in contrast to the nomadic life of the previous hunter-gatherers. It seems likely that river valleys were choked with dense wild woodland, while the hilltops might have supported lighter woodland giving way to open grassland in places where men had started clearing the tree cover. Herdsmen (or women) may have moved their animals to higher pastures in summer, thus retaining a semi-nomadic lifestyle, and hunting, especially in winter, would still provide an important source of food. There is evidence from a site near Parwich to support this view:

By the Bronze Age, Dimbleby concluded, the hilltops were open pastures where limited cereal cultivation was practised, but patches of woodland and scrub, much as today, grew nearby. Thus tracts of upland may have been exposed by the Later Mesolithic period, but the valleys were in all probability still thickly wooded.

Hodges, R. (1991) Wall to Wall History: The Story of Royston Grange.

It is generally assumed that the very first tracks were made by wild animals, in search of food or water, and that these were then used by hunters. Then, when settlements sprang up (which would also have been on the higher ground), these paths were modified into a network linking the farmsteads together. Clearly a prehistoric landscape of farms, moors, woods and ceremonial sites needed roads for many of the same reasons that we do today, both for local and everyday traffic as well as long-distance travel.

See the order page for information on how to get hold of a copy.